Many a truth is inadvertently spoken in clumsy translation. At least two good examples appeared in the marathon goody-bag I collected from the expo on Friday. One of the pre-race instructions, intended kindly no doubt, is “Don’t forget to say goodbye to your friends and family before you start the marathon”.

They mean “Don’t clog up the start area”, but their version has a sense of dire finality that will resonate with certain participants.

Make no mistake, Hamburg is a truly great urban marathon. The crowd support is fervent and loud, and without meaning to invoke unreasonable racial stereotypes, it’s no surprise that the organisation is simply flawless. Here, there are no untied ends to stumble over.

I felt irrationally confident about this one from the moment I awoke, at 3:50 a.m. It wasn’t excessive enthusiasm or nervousness that dragged me from my slumbers at such a twirly time, but the return of the two blokes in the next door hotel room. English, naturally. I’d engaged them in uneasy conversation earlier in the day, when I’d discovered the main objective of their visit: “The search for the ultimate bender.” They went on to explain that there had been 14 on the party but that two of their mates had “disappeared” last night. I didn’t think it decent to enquire further.

I mentioned the marathon, and tried explaining that I needed a good night’s sleep. But I could see from their glazed eyes that I sounded like some middle-aged keep-fit bore whose only pleasure in life was trying to avoid death. Somewhat implausibly, they promised to be quiet when they returned from their 8 hour piss-up on the Reeperbahn. Which is why I wasn’t too surprised to be woken by the sound of them clattering back to their room at ten to four in the morning. They were singing heartily. No chaps, this isn’t the f***ing way to Amarillo…

And that was that. They quickly fell unconscious, but it was too late for me. I didn’t get back to sleep.

Good old Hal Higdon. His advice is to ensure a good night’s sleep the night-before-the-night-before the marathon. This is the important one, says Hal. Adrenaline, he says, will get you through a disrupted sleep the night before the race, but only if you have something in reserve from the night before. This advice saved me. If you can call it salvation…

At least the first half of the day was a resounding success.

At 6 a.m. I couldn’t put off the inevitable any longer, and got up to start the pre-race sacramental rituals. The taking of the currant buns and bananas, and the final glass of water. Naked, in the dark. Then a dribbly shower that seemed more of an annointment than a cleanser. The silence was louder than the shower.

M slept on.

I peered through the curtains at the scene below. Hotel Kronprinz is in Kirchenallee, directly opposite the main Hamburg railway station, and even at 7 a.m. there were plenty of people in trainers, carrying their plastic, drawstrung baggage, striding purposefully across the pedestrianised square towards Hauptbahnhof, the central station, just three stops on the Underground from the race start.

Where did this Bodyglide come from? Goody-bags melt into each other, just like the races to which they belong. I don’t know where I got it, but I’ll give it a go. Feet, thighs, nipples. Adopting a belt and braces approach, I give the Bodyglide a patina of Vaseline. Then it’s the lycra undershorts. The singlet I bought at the Chicago marathon – the one with ANDY inscribed on it. Thorlo socks. I’ve had these socks ever since the London marathon campaign in 2002. Reebok shorts. These are even older. I bought these in Oxford Street in January 2001, the month I thought I’d try running. They’re nearly dead. The webbed innards have disintegrated under the relentless torrent of corrosive scrotal sweat and other, less respectable corporeal exudations. The original navy blue has now been bleached by effort into something less bold. They even have splashes of paint on them. But I stick with them, for reasons partly practical – they have two large pockets – and partly sentimental – we’ve travelled a long way together. Hamburg is my 31st race, and I’ve worn these things in every one, as well as on training runs that can be counted in their hundreds.

Where did this Bodyglide come from? Goody-bags melt into each other, just like the races to which they belong. I don’t know where I got it, but I’ll give it a go. Feet, thighs, nipples. Adopting a belt and braces approach, I give the Bodyglide a patina of Vaseline. Then it’s the lycra undershorts. The singlet I bought at the Chicago marathon – the one with ANDY inscribed on it. Thorlo socks. I’ve had these socks ever since the London marathon campaign in 2002. Reebok shorts. These are even older. I bought these in Oxford Street in January 2001, the month I thought I’d try running. They’re nearly dead. The webbed innards have disintegrated under the relentless torrent of corrosive scrotal sweat and other, less respectable corporeal exudations. The original navy blue has now been bleached by effort into something less bold. They even have splashes of paint on them. But I stick with them, for reasons partly practical – they have two large pockets – and partly sentimental – we’ve travelled a long way together. Hamburg is my 31st race, and I’ve worn these things in every one, as well as on training runs that can be counted in their hundreds.

And then those blasted shoes. In the interests of a fair historical record, I should say that they felt OK on marathon morning. Not bouncy and pumped up, but at least sort of grizzled and sinewy and businesslike, and ready to pull out a final performance for the old man.

Then it’s the velcro chip strap, bought at the expo. Something similar came free for the Reading Half, and I liked it. I’m intimidated by those naked chips you get that you’re expected to thread expertly through your laces, rendering them impossible to remove after the race without dissecting your shoes. Or is there some masonic technique imparted to the rest of the running world that passed me by? I don’t like to ask.

A chip strap has a band you tread through the chip, before velcro-wrapping the whole thing round your sock. Simple.

Last item is my canary-yellow Hal Higdon cap, worn partly to keep the sun out of my eyes, and partly to make it easier to recognise myself in the later stages of the race. Just imagine it. Mile 23. Crowded, chaotic water station. Disoriented, you look round, desperately trying to work out which one you are. Answer? Yellow cap. Works every time.

The plastic sack gets filled with…stuff. My personal effects. A fleece, a notebook and pencil, a solitary Compeed, Bob Glover’s Competitive Runners’s Handbook. (He’s the bloke who wrote it, incidentally, not the one who lent it to me – just in case there’s a non-runner reading this. It’s just that “Bob Glover” sounds like a retired Geography teacher, or the chap who runs the village bicycle repair shop – the sort of rotund, balding chap who’ll engage you in conversation over the garden fence on a Sunday morning, in the middle of mowing the lawn. That said, probably not the type to own a book called The Competitive Runner’s Handbook. But I digress…) Some headache pills. Mints. Water. Contact lens solution. Vaseline. Towel. None of it’s necessary beyond the fleece. The fleece is the one thing I need to take, but a baggage sack with just a fleece in it doesn’t seem right. Too light and unimportant. What if? This is a marathon and this is Germany, and today I am… Herr Onze-Sideofcaution.

Tiptoe to the door. Before turning the handle, I look round. M is still asleep. What now? Oh. Do I wake her just to say goodbye? Am I superstitious? What if I die during the race? Waking her – inconsiderate or considerate? Would it be for her benefit or for mine?

I bequeath an affectionate glance, and depart in silence.

Any lingering bubble of melancholy is popped as I pass the room of the lads next door. Oh, this is funny. They didn’t quite manage to complete their Saturday night lives. It’s like a scene from the last moments of Pompeii, with the townsfolk frozen in their final agonies. The door is wide open. One guy sits sprawled in an armchair in his Y-fronts. The other fully clothed, half kneeling, half lying across his bed. So near, yet so far. Both snoring loudly. Thank you god.

Just like London on marathon morning, the Underground is flooded with people on their way to the race. Spectators seem to be over-dressed to compensate for their running partners. Ever noticed that? They wear overcoats and do a theatrical shiver from time to time, as though to send some subliminal message to their companions. Admonitory or sympathetic?

And so to the starting pen of the 2005 Hamburg Marathon, where only the first timers will be overtly nervous. Most of the rest display a touchingly naive optimism. Here are the grizzled, sinewy old timers looking complacent. The muscley young athletes, brimming with testosterone, but too cool to be seen looking over-excited. Another group, the one I belong to, are those who aren’t marathon virgins but still struggle with the reality of what we are about to receive. We aren’t dumb. We’ve made the effort to discover the ingredients of a successful run, but haven’t had the time, the determination, or the nous, to acquire them all. Some of the preferred constituents, like youth, are no longer available to us, and we must do the best we can without it. Others, like ideal weight, are available, but hard work. Family life, self-esteem, effort, equipment, motivation, freedom from injury – all are members of this multi-conceptual cocktail. Perhaps we don’t try hard enough, or perhaps we try too hard. Or maybe the effort is high enough, but we don’t get the recipe quite right. I suspect that’s it.

I don’t hear the starting gun in Hamburg, I just hear a wild shriek. It’s an apt substitute.

When you start your marathon training, the finish line seems like a very distant shore indeed. Yet now, one of the 33,000 shuffling towards the start, it seems somehow even further away. Before today it’s all hypothetical. Now it’s real, and it becomes a quite different challenge.

Just before I cross the line, I notice an earnest looking, grey-haired man holding up a piece of cardboard on which he’s written in ballpoint pen: PAIN IS TEMPORARY, PROUD IS FOREVER.

This time I have a firm strategy. Yes, it’s probably the same firm strategy I had in Copenhagen and Chicago and in London. Last time it didn’t quite work out, but this time it has to succeed. This time I’ll see it through. The magic numbers are 6:45. That’s to be my kilometre pace, and it should be easy to sustain…

There’s a mild panic when my watch says 7 minutes, then 8, with no 1 km sign in sight. When it reaches 9 minutes, I relax again. I must have missed it. Sure enough, 2 km appears, on 13:10, giving me the luxury of being able to slow down for a few seconds as I pass the sign.

Some people spurt down the Reeperbahn, but I prefer to dribble, taking in the curious sights. We pass bars called The Blue Banana, Blue Nights, Blue Touch, Blue Moon. A shop called Bad Meets Evil. And the name that represents a passport to international eating pleasure: Kentucky Fried Chicken.

The weather was just about perfect for a marathon. Cool and bright.

The Hamburg spectators were magnificent from the start. The usual estimate is around half a million people, though I don’t know how such a figure is arrived at. There’s something rather too… round about 500,000. My instincts say that there were fewer (just) here than in London in 2002, though this lot seemed crazier and more noisy. Percussion of all kinds, ranging from kids gleefully banging saucepan lids together, through dreamy tabla players, right up to the ferocious Hells Angel thundering out his weltschmerz on a full size drum kit by the side of the road.

Second to percussion came wind: whistles, flutes, harmonicas and even a tuba or two. Most didn’t bother with any implements at all. Vocal chords are pretty good at this noise thing. They hollered and raged with delight and excitement. Today we are all demented pedestrians, and today we’ve taken over the city. In a world of subtle suppression, a marathon may be as close to anarchy as we will ever see. It becomes a temporary public expression of a youthful zeitgeist normally half-concealed.

Second to percussion came wind: whistles, flutes, harmonicas and even a tuba or two. Most didn’t bother with any implements at all. Vocal chords are pretty good at this noise thing. They hollered and raged with delight and excitement. Today we are all demented pedestrians, and today we’ve taken over the city. In a world of subtle suppression, a marathon may be as close to anarchy as we will ever see. It becomes a temporary public expression of a youthful zeitgeist normally half-concealed.

Those early miles were just grand. Absolutely capital. Through the pandemonium, we ran through the cool, shady streets of Sen and Altona, beneath the pollarded trees and the tall, elegant apartment blocks. Not for the first, nor the last, time today, I feel strangely European.

I find myself bopping alongside Running Rock Man for a few minutes. Running Rock Man pushes a portable music player. Some kind of massive speaker on wheels. It’s blaring out “Sweet Home Alabama” by Lynyrd Skynyrd. It keeps me buoyant for a few minutes, but I decide that the pleasure may wear thin after an hour or two, so I let him go ahead of me. The next musical interlude is Aretha Franklin squawking “Freedom” from a sound system dangling over a balcony. This song is laced with something infectious, and something akin to hysteria spreads quickly through the runners as they pass. Much whooping and twirling and clapping. For a few surreal seconds, we’re a scene from “Fame”.

A man with a carrier bag of live, wriggling eels holds one out to tempt passing runners. The women squeal and he cackles.

Amid the abandon and the chaos of the honking horns and the roaring and whooping, you catch glimpses of the other world. The expressionless, elderly lady dressed in black, peering down from another apartment balcony. What is she making of it all? I wondered this from time to time through the race, and wondered what else she had seen in her life.

It’s so easy to fall into the pattern. All is cool. Cool urban running and cool accoustics. This is running as relaxation. I could have had a brief nap without falling over. I’m shocked when someone suddenly calls out my name. Three or four women with painted faces are shouting my name hysterically. Ah yes, name on my shirt. I’d forgotten.

The long pleasant Konigstrasse and Bernadottenstrasse take us up to the 6 km mark, and here we swing round in a sharp U-turn, back towards the city centre. This next 5km sweeps us along the Elbchaussee, the dock road. The docks? In most cities this would evoke a desolate, pot-holed plod through a depeopled landscape of warehouse complexes and pyramids of rusting containers. But this is Hamburg, and here the docks are a feature. This long stretch along the waterside and the giant cargo ships is Millionaire’s Row – one of several in the city. Yep, container ships really can be sexy. Porsches and Mercedes line the driveways, and even if the spectators here seem more well-heeled than in the opening stages, they are no more restrained.

Around 10 km, the road suddenly dips and enters a gentle but long, long decline, and below me a sight that makes me catch my breath. The shot so beloved of the TV camera: it’s that tidal wave of bobbing heads; each one of us a different coloured bit of flotsam on that rolling ocean of runners. It’s the moment I’ve waited for – the moment when all that ever is and was and will be about this place on this day in this race, is packaged up and presented to me, ready to take home and admire for the rest of time, while all else will be left to fade.

Three young English runners are chatting behind me as we curl down the hill, alongside the gigantic ships hooting their way out towards the North Sea. I catch fragments of their breathless conversation. “I’m so glad I missed out on London now”, says one. “Just think, we’d never have seen all this.”

It’s an interesting comment. The London Marathon is a great race and a great occasion, but I challenge the assumption held by many that it’s the only marathon worth doing. People: get out more.

We pass the imposing Fischmarket and sweep left along Hafenrandstrassen towards Jungfernstieg, the exclusive shopping district. Then past the superbly-named Rathaus (local parliament). Then we sink into a deep and dark underpass behind the main railway station, and find ourselves running beneath the city centre. It’s a strangely intimate stretch. Dozens of people, men and women, take the opportunity to ‘do a Radcliffe’, and urinate. No one minds peeing in front of other runners, apparently.

We re-emerge alongside the Art Gallery and here I see M, squealing in a very un-M-like fashion. She takes a couple of corking pictures. What I like about them is that they seem to convey just how good I was feeling at this point. Most race photos look like something you might find in a post-mortem file.

We’re about 17 kilometres in now, and everything is marvellous. I feel strong and capable and confident. My pacing is still spot-on. I seem to have discovered the secret of marathon running. Let me rephrase that. I always knew it, but this time I’ve decided to act on it. Even pacing. As long as I can keep this up, I’ll be fine.

We exchange waves and whoops and I press on through the city and up around the Alster Lake. There’s something calming about this placid, turquoise expanse of water with its tall, spectacular fountain. Like the Maidan in Calcutta, it’s ‘the lungs of the city’. Perhaps it’s the sight of the water but now I’m sweating heavily. The sun that was just bright at the start is still bright but now it’s burning too. I notice that I’m taking on far more water than normal. Usually I have a couple of sips at each water station. Here, I find myself swallowing two full cups every couple of kilometres. This was the first warning that something might be going wrong.

The next mile or two slowly drag us north through the modern, elegant suburbs flanking Beethovenstrasse. The kilometres seemed to be getting longer, though my watch told me I was still on target pace. The first 10K were covered in 01:07:13, the second 10K were 7 seconds faster, 01:07:06.

But as I got past the 20, the inside of my thighs were beginning to hurt, and as we crossed the half way mark, just a mile or so later, they were tight and aching. Really aching.

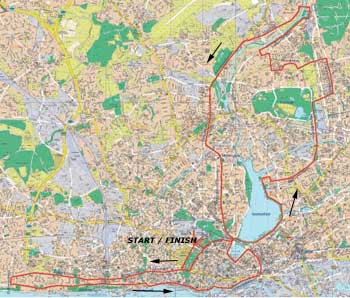

That was the first half of the race, and that was… just about… the race. What happened in the second half? I can look at a map of the course, and I can see the route winding its way north through Uberseering and Rathenaustrasse and then, around 30 km, tipping over and plummeting south towards the distant finish line. I recall being there, struggling along, half walking, half running, but little has embedded itself in my memory.

I was kaputt. My upper legs had seized up, and I was juddering along like a drunk on stilts. The legs weren’t bending in the middle. It was painful, but there’s nothing heroic to report. It actually became rather boring because I didn’t seem to be getting anywhere. Sweet songs never last too long on broken radios. I couldn’t get that line out of my head. It was supposed to be the day of the Übermensch – Nietzsche’s Superman – but instead I’d become John Prine’s wretched Sam Stone.

What do I recall from this second half? I recall a blind man sitting beneath a weeping willow, playing the pan pipes. I remember passing a colossal amplifier through which a grinning rastafarian was thundering a bass guitar. The street vibrated beneath my feet as I passed.

Above all, I remember feeling disappointed. I remember thinking that it’s not failure that threatens us. It’s optimism. It’s things we’ve never had. We are haunted by hope, and it’s hope that truly destroys us. It was a feeling that lasted for nearly ten desolate miles. The game was up.

I wasn’t deranged or hallucinating – unfortunately. That would have been some minor consolation. Something had gone wrong, I knew, and I struggled to know what to do. For a while I tried to be practical. Next time, there should be some gym work and leg-strengthening exercises. Perhaps more hills…. And these damn shoes – must improve shoe strategy. Did I blow it all with an inadequate final week? Maybe I should have tried even harder to shift a few pounds. I had to listen to this loose change of censure and self-castigation jangling around for miles, knowing that these weren’t really the solution. The marathon is more than a race; it’s a puzzle, a game, a riddle. Perhaps I’d never find the answer. Suddenly, the very idea of another one of these things began to seem remote and pointless…

But there were high points during those last 10 or 12 miles. The crowd remained sensational. They had more energy than the runners, and some of it did seem to transfer over to us. Frequently, as I stopped to walk, I found myself being cajoled and clapped and shouted at by knots of cheerleaders. And they made a difference. More than once, I ended up clapping them, as they lifted me back onto my running feet.

But the one really remarkable example of mind over matter came around Mile 21 when, for no reason at all, I had a flashback to the start of the race. That elderly man with his sign, and the spindly, charming misspelling. PAIN IS TEMPORARY, PROUD IS FOREVER. It hadn’t registered much at the time, but it had been filed away somewhere, and now, when it was needed, it popped up. It’s the oldest marathon cliché in the book, but as it came to me now, I really did feel something stirring. I’d heard it said a thousand times but perhaps I’d never given it much thought. I thought about it now. We always say that the last few miles of a marathon make you hyper-emotional and vulnerable. I think it’s caused not by too much emotion but by too little. It’s an evacuation of the senses, not a filling up, and it’s this vacuum that sucks in whatever sentient fuel is going.

It was in this state of emotional impoverishment that the image of the man with the sign arrived, and it hit me with a thud – a very positive thud. Something spread from my head to my legs, and for 10 minutes I really did run again. Here’s the proof.

For first 14 miles of the race, my times were:

10:45

10:51

10:36

10:41

10:55

10:46

10:55

10:43

10:39

10:32

10:29

10:41

10:32

10:57

With a target pace of 10:50, these splits are fine.

Then at mile 15 it started to go wrong:

11:42

12:22

11:19

12:35

13:29

13:38

Into mile 21, and my PAIN IS TEMPORARY, PROUD IS FOREVER moment happened.

The split for mile 21?

09:22

But I couldn’t keep it up, and the last 4 miles came in as:

12:31

13:33

13:50

13:16

By mile 17 or 18, I knew that I was going to miss out on my main target of getting round in under 5 hours. I’d have to accept that, but it never occurred to me that a PB wasn’t going to happen. My previous best, 5:16 in Chicago, had to be beaten today. And it was. As the miles ticked down, I was pretty sure I would do it, and this was a great consolation to me. In the end I made it home in 5:10:10, 6 minutes faster than Chicago.

Other stats:

10km: 01:07:13

20km: 02:14:19 (01:07:06)

30km: 03:30:14 (01:15:55)

40km: 04:51:43 (01:21:29)

The figures show how those first two 10K stretches were bang-on, separated by just 7 seconds. But then the third 10K drifted out almost 10 minutes, with the fourth a further 6 minutes slower.

And there, in two short sentences, is the story of my Hamburg Marathon 2005.

Through the finish line and floated back into the expo hall to cash in my chip and generally enjoy that fuzzy post-marathon feeling. I wandered out again and into a Turkish supermarket to buy a bar of chocolate. There was a small internet café at the back, so I took the weary opportunity of letting the chaps on the forum know how I’d got on.

On the Underground back to Central Station, I worked out my post-marathon training schedule. Just as one needs to train for a marathon, one needs to train for no marathon, I reasoned. I still have my plan sketched out, here in my notebook. It says simply: SAUSAGE – BEER – SHOWER.

At the station, I chomped on two bratwurst with chilli and emptied a couple of beers down my throat, while staring blankly at a TV screen. Some unknown people were playing football on it. Then it was the awkward totter back to the hotel for a shower and a long, contemplative soak. Hamburg was over.

It’s a great marathon, and one I’d recommend to anyone – novice or elite. The course is pancakacious, a nailed-on PB for anyone in reasonable shape. The crowds are wild and wunderbar. On the day it didn’t quite happen for me the way I wanted it to, and the way I expected it to. Right up to halfway through the race, I thought this story would have a different ending. But if our stories always had predictable, perfect endings, joy would soon become wearisome. I wasn’t going to let this slight disappointment turn into a disaster. It wasn’t a disaster. I knocked 6 minutes off my PB, and it was my 5th PB in 5 races. That’s enough to make it a success, and if not utterly elated, I could at least be satisfied.

Eventually I was able to winch myself out of the old-fashioned, high-sided bath and delicately pad myself dry. The aches were coming.

There’s only one thing you can wear on the top half after a marathon, so I pulled on my commemorative race tee-shirt and lay on the bed. As I said at the start, many a truth is inadvertently spoken in clumsy translation, or cultural confusion. On the teeshirt, beneath the Hamburg Marathon 2005 logo, is just one word in large block capitals: FINISHED.

Lying there on that sunlit afternoon, high above the city, floating away into weary unconsciousness, it was the perfect summary.