A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.

It took me until halfway through the Copenhagen Marathon to adopt a hybrid of 99 Red Balloons and Mister Tambourine Man as the soundtrack to the day. By contrast, Zurich Marathon day was just a few seconds old when I found what I really didn’t know I was looking for.

I heard the sound of a thunder, it roared out a warnin’,

Heard the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world…

Alarm goes, eyes creak open. I’m lying there in the darkness for a few moments, semi-conscious, hearing a noise I didn’t want to be hearing; the unmistakable sound of water drumming against the slanted window. Just like the Almeria Half in January. And the Wokingham Half and the Bramley 20 in February. Miserable, sodden races every one.

Breakfast. Everyone I met seemed to be called Morgan, which was odd. Apart from these perfunctory introductions, it was a non-speaking, contemplative occasion. Just the languid munching of toast and muted tintinnabulations of spoon on muesli bowl. Solitary men, gazing through the French windows at the rain sploshing over the abandoned barbecue tables. We were a scene from some monochrome Ingmar Bergman film.

What a contrast with that Copenhagen race, two years ago, when the marathon breakfast was a high-fiving, clamorous, jubilant, sun-filled affair.

I looked around. French guy in a crisp new Asics tracksuit. Bright red. On his feet, some items that had probably been marketed as pre-race sports slippers, and sold at 10 times the price of poncified flip-flops, which is what they actually were. He seemed so darned intense that I wanted to beat him on the head with one of those mega Toblerones you see at airports.

As I was leaving, I walked into the kitchen and thanked the three bleary-eyed staff for getting up extra early for us. One of them looked like he could have burst into tears with gratitude.

Returned to room to find my wife had exploded. I was taken aback. We’d eaten the same food for 48 hours, but something had got to her that had left me alone.

Stepping outside the hotel into the rain. Bollocks, it was the wet stuff, too. The really wet stuff. Not a subtle spray or a sporadic drizzle, but big heavy plops of cold water. I walked up through the maze of quaint, variegated terraces behind the hotel. Seven thirty, and no one else was around. No cars nor people nor cats. No movement or noise beyond me and the weather.

By the end of the first street, just as I reached a critical crossroads, my map had melted in the rain. I took a left, but 20 yards on, a German voice called out. I turned around to see a smiling young couple with carrier bags on their heads. They’d just emerged from a snicket between two shops. In their hands were marathon bags. I said something apologetic in English. She giggled. “This way please!” I followed them up the steep hill opposite. We all grinned, but said nothing more.

The routine had begun two days ago. Arriving in a new city, a new country, light-headed with sleeplessness. The bus ride through undulating, sunlit suburbs, full of calm people and shops with unfamiliar names.

Hills, eh? I suddenly wonder if the marathon will be flat. I’ve assumed it will be, as most of it is around the lake, but I don’t know this for sure. The hotel, clean and pleasant, but never quite as spacious, as minimalistic, and as palatial as the pictures suggest. But not bad at all. When we insert the key card in the slot by the door, the blinds automatically rise, revealing a terrace overlooking a neat garden below.

I lose the battle with the coffee machine. All I get is lukewarm, weak stuff, when I should be getting he-man shots of espresso. So we flick through the TV channels and doze. I would never dream of watching CNN at home, even if it was available. But in another country, it’s the least foreign channel there is.

Short walk, under the flyover and the small river to the Sportshalle, and the Zurich Marathon Expo. This time it really is a sports hall, and not the usual conference centre. A small arena with a dozen or so rows of tiered seats around it. The central area has been given over to perhaps 20 stalls, including a long one at the end where chips and numbers are collected. There is hardly anyone around. There are maybe 30 runners on the premises while I’m there. It’s Friday, and will doubtless be busier the next day, but it reminds me that this race is a much smaller affair than Hamburg or London or Chicago, all of which boast in excess of 30,000 runners. Here in Zurich, we are 8000, an increase of 1000 over last year. It’s only the 4th year it’s been run, and they are slowly building their strength and tolerance, a bit like the runners themselves have had to do over the past few months.

One nice touch – the race numbers include the runner’s first name. It’s seems like a reflection of the innocent excitement attached to the event here. A big city marathon shouldn’t be a poker-faced affair, and these people have had the independence of mind and just enough sense of mischief to make that lightness of spirit official. Switzerland isn’t

in the EU, and it shows.

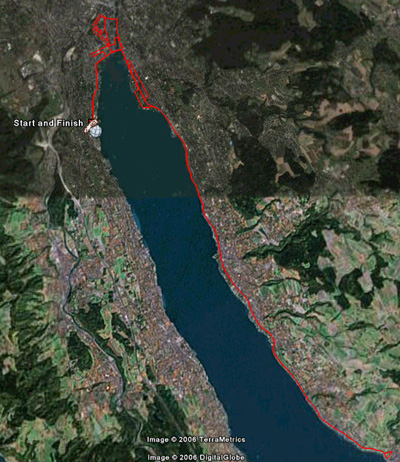

The day before the race, we get on one of the tourist buses for a 4 hour trip around the city. I’ve requested a relatively relaxed day, free from gallery-pounding and unnecessary time on my feet. It’s a good way to spend the time – checking out the marathon route in advance. Not everyone would agree with that, saying that it may just add to the fear factor. But I’m big on visualisation at the moment, and this is helpful.

On the bus we find ourselves right behind an extended Cuban family from Florida, laden with iPods and attitude. Maybe they just flew in last night, and are still jet-lagged. Ten minutes in, and 8 out of the 9 in their group are sound asleep.

Zurich is small and civilised, a confident modern city built around a medieval core. It’s my first trip to Switzerland, and this pretty much matches my expectations. Cobbled streets in the centre, monolithic churches, clanging trams and exotic chocolate shops. The people are busy and courteous, and not very fat.

After the city sights, the bus winds its way round the western shore the of Lake Zurich, and on up the opposite hillside to the cable car station. We glide to the top, marvelling at the huge silver mirror of water glittering in the strong spring sunshine. Up here, dwarfed by the steep hills and the lake, the old city looks even smaller.

The sassy Cubans have woken up now. At the top of the hill they react to the discovery of snow the way that Texans would at the discovery of a new oilfield. Much whooping and punching of the air – and of each other. They’ve never seen this stuff before.

Later in the afternoon we take the ferry across the lake to Meilen, which I realise is the turning point of the marathon. We are to run out to here, double-back through the village and return along the same road to the city centre. The bus now takes this route, and I am eager to see the sights I may miss tomorrow. I’m relieved that the road is wide and

well-maintained, and apart from the odd tiny slope as we enter and leave each in the line of villages, would seem well placed to teach pancakes a thing or two about flatness. To my left, the lake sparkled, and a thousand yachts bobbed in the faint breeze.

The next time I see the lake is marathon morning, from the top of the footbridge across the road alongside the start. This same stretch of water is now grey and choppy and menacing.

The next time I see the lake is marathon morning, from the top of the footbridge across the road alongside the start. This same stretch of water is now grey and choppy and menacing.

The rain was tipping down, and I had to watch where I was putting my feet. Twice in a minute, I almost lost my balance. Once on this bridge, and once on the greasy steps into the underpass beneath the railway line.

I thought how lucky I’d been with injuries in this campaign. Several twinges and aches had threatened to snuff out the marathon over the

past few weeks and months, but none had been carried through. Now, on marathon morning, my two near-slips, plus M’s food poisoning, had

reminded me that disaster can strike at any time up to the starting gun. Any of these could have stopped me reaching the start, but who would have believed me?

Beyond the railway line is a potholed path along which hundreds of plasticated runners were trying to pass. On our left, the changing rooms, but they were shut. People stood around outside in varying

stages of quivering nudity. None looked over-jovial.

Further along the track, a row of old railway wagons was serving as the baggage storage facilities. My number, 6510, took me to the far end of the line. Reaching it was chaos. The narrow, uneven path was covered by deep puddles, so everyone who used the baggage drop for this race (probably a large proportion) would, like me, be starting this race

with cold, drenched feet.

I was already wearing my kit, but had to find a spot to deal with necessary last minute adjustments. Off came the waterproof jacket and the fleece, and the tracksuit bottoms. On went the old teeshirt over my race singlet to give me some temporary warmth, and another priceless waterproof layer.

After the Brighton 10K debacle, I’d resolved to invest some thought in the bin-bag area of my wardrobe, and it was with a sense of pride and anticipation that I now pulled out the B & Q Deluxe Garden Refuse Sack With Super-Strength Handles. And in fetching racing green, too. The shivering Italian to my left regarded me with envy and resentment. On this bin-bag catwalk, I was exhibiting the Gucci creation, while he was Man at C & A.

It wasn’t easy to find my place at the start. I was in the slowest, blue category. The normally efficient Swiss hadn’t indicated the starting pens, or if they had, not very well. So it was left to me to find the pacing groups. Eventually I spotted the red balloons of the two 4:29-ers, and clambered over the railing.

It was a scrum in there. Minutes before the appointed hour of 8:30, anxious runners were still trying to make their way against the human tide to reach the baggage buses. The umbrellas of the spectators lining the path were deflecting rain down the backs of anyone trying to squeeze past. It wasn’t pleasant. Was the monument embodying the Swiss stereotype starting to develop cracks? Not really. no. It would be wrong to be too critical of the organisation. In my extensive experience of wet-weather racing, most of it acquired in the last 3 months, it seems that no race organiser has yet found a way of dealing with heavy rain. What can you do? It slows the machine. It subdues thousands of people who would otherwise be whooping and high-fiving – literally in the case of the Americans, perhaps metaphorically for the Europeans. It delays transport, which delays people getting to the start. It makes puddles to step in, and to fill your shoes with cold water. There were no major defects with the organisation. They, and we, drew the short weather straw, and there’s nothing for it but to accept it and get on with the task.

It seems that we do this in different ways. Many of my fellow runners coated themselves in plastic for the entire race. At a minimum, most wore leggings and long sleeves teeshirts. The braver ones stripped down to shorts and just two top layers – teeshirt and singlet.

And then there were the Africans. And Me. We were the ones wearing just shorts and singlet.

But waiting for the starting gun, I retained the flimsy cotton teeshirt and B & Q Deluxe Garden Refuse Sack With Super-Strength Handles. The latter stayed on until the gun sounded at exactly 8:35. As usual, at my end of the field, the great roar that goes up is immediately followed by 5 minutes of inertia as we wait for the faster entrants to get out of our way.

Eventually we begin a first-gear trudge, during which I say farewell to my B & Q Deluxe Garden Refuse Sack With Super-Strength Handles. Lovely while it lasted. Beneath the inflatable arch and across the squealing chip mats. Game on.

For the benefit of anyone who hasn’t read previous entries, I’ll mention that the Zurich Marathon has a strict 5 hour cut-off. Anyone falling behind that pace “will be invited to leave the course”. My marathon PB was 5:10. I didn’t want to be invited to leave the course, especially as Sweder of this parish and I have talked about doing the Two Oceans Ultra Marathon next year, for which you need a sub-5 marathon qualifying time to enter. I’d like an autumn marathon to be an option, not a necessity.

Talking of Sweder, I now remembered that at this precise moment, he would be going through something very similar at the start of the Paris marathon.  Marathon runners are egocentric animals. So wrapped up are we in our own doubts and our own excitement, that we forget about the other thousands exploring their own self-built hell. Good luck Sweder.

Marathon runners are egocentric animals. So wrapped up are we in our own doubts and our own excitement, that we forget about the other thousands exploring their own self-built hell. Good luck Sweder.

A cut-off concentrates the plodder’s mind. I’d thought a lot about race strategy in the past 2 or 3 weeks, though I wasn’t certain where this had got me. I’d looked at the facts. My marathons and longer runs had always followed the same pattern. First half strong and confident, second half weak and faltering. Pace didn’t seem to matter. If I started quickly, I got slower. If I started slowly, I got even slower. But how much slower did I get after a fast start, and did this wipe out the advantage built up by that faster first half? Add in the rain (negative influence) and the desperate need to beat the cut-off (positive) and it got even more confusing.

As the race approached, I’d decided to defy all the advice I had ever given to first time marathon runners:

“Start slow, then slow down.”

“If you start too quickly, you’ll burn out.”

“Aim to run each split at the same pace.”

I ignored all this. I crossed the start line, and immediately moved to my 10k pace. Would I get away with it? To get round in under 5 hours I had only to manage an average of a kilometre every 7:07 minutes. It is very easy to run a kilometre in this time. The trouble I would have would be to maintain

that average 42 times in a row.

The start of a marathon is like an army leaving the garrison, marching off to some distant war, leaving a trail of wailing relatives in its wake. All of these marathoners would make it back of course, even if few would find themselves to be precisely the people they were when they left. It’s hard to think of many activities that alter your state so fundamentally over a few hours.

As I crossed the chip mats, I glanced over my left shoulder and saw the 4:29 pacing group right behind me. Within a couple of hundred metres I knew I’d left them behind. I wasn’t to see them again until the second half of the race.

It was also the one and only time I looked behind me in this race. I’d been careful not to over-hydrate before this race but it was no good. Shortly after we set off, that familiar tickle began. I needed a pee. Perhaps it was all that rain that was inspiring me. But wait.

Public urination in Switzerland? Wasn’t this the sort of social outrage that populated an entire wing of the city jail? The prospect worried me. But as we chugged through that first kilometre or two, I grew emboldened by the sight of dozens of runners stopping off in the bushes alongside the lake, or ducking behind hoardings to satisfy the bladder’s pleading. After 3km I stopped off to express myself behind an abstract statue in front of the corporate HQ of… well, of one of my

biggest customers. I resolved to apologise at a later date.

Still it rained. By now I’d dumped the teeshirt and was running in just singlet and lycra shorts. Rather daring for me, but I was trying to be a well-oiled, ultra-efficient running machine, and lycra shorts helped to nourish my delusion. As I pulled off the teeshirt to reveal my Reading Joggers singlet, a voice alongside me asked “Is that Reading in England?” I chatted with the lady from York for a minute or two. This was her first marathon since returning from a long injury lay-off. I was surprised to learn that she was planning on doing the London Marathon in just two weeks time. Like me, she was worried about missing the 5 hour cut-off. I wished her luck and went on ahead.

There wasn’t much conversation in this race. A middle-aged, shaven-headed guy spoke to me in excitable Polish on around 5 miles. I remember glancing sideways at him, and seeing the rain bouncing off his head like a tap dripping on a hard-boiled egg. I said something in English, and he shouted “Ah! Marathon! Marathon!” and ran off, laughing hysterically.

The first seven miles zipped by in 09:36. 09:33, 10:17 (including pee stop), 09:34, 09:39, 09:43 and 09:29. By my standards, this was breathless stuff, but I knew I had to keep it up as long as I could. Every fast kilometre and mile now, was giving me a cushion for later in the race. According to my GPS watch, I passed the 10km point in 59:58, which if true, is actually the first time I’ve done this distance in under an hour. But I don’t think those unwritten rules allow me to count it as a PB.

Around this point I first became aware of a creeping muscular pain in my left shoulder. I put my right hand over the area, and was struck by how cold the shoulder was. With my hand on it, the pain vanished. When I lifted it, the pain returned. I wasn’t sure what had caused the problem. The other shoulder didn’t hurt in the same way, and felt warmer to the touch. I became more aware of it as the race went on; the pain never went away.

Most of the race route took us along the lakeside road, though a combination of the weather and the marathon mindset concealed most of the scenery. It’s often said that marathons show you a different side to a city or a landscape, but I’ve started to doubt this. A marathon route usually does take us places off the tourist track, but we’re in no state to enjoy them. Just taking an interest in your surroundings actually uses energy, I’ve realised. And more gets spent on talking to

other runners, swapping banter with spectators and applauding the bands. I do all of these things, but Zurich brought home to me how energy-sapping these simple activities are. It’s a disappointing realisation. I look forward to these things. Worse, it seems impolite not to acknowledge the bands and the spectators who offer encouragement. If I don’t, they may stop.

Why was I surprised by the enthusiasm of the Zurich spectators? Somehow I’d come to Switzerland with the idea that these people were deeply conservative and undemonstrative. Not so. The rain doubtless kept many away, but those who did turn up were loud and positive. If the Spanish are animaux-merchants, and the Americans inveterate whoopers, the Swiss are hup-hup-huppers. Wonder how many times I heard that during the race? Hup-up-up-up! .

Some rang bells or blew whistles or bashed things together. Britons don’t go a bundle on making noise by banging things together, but those chaps over the water are certainly keen.

The guidebooks describe this stretch of the lake as the Golden Coast. Less to do with the extra sunshine it is said to receive than the wealth of the residents living in the unbroken chain of villages running into each other: Zollikon, Kusnacht, Erlenbach, Herrliberg and Meilen, the turning point. I was never quite sure where one finished and the next started. I can confirm that the spectators here looked well-fed and rather pleased with themselves. Zurich is evidently good psychological preparation for the Burnham Beeches Half. And why shouldn’t they be satisfied? They live in a beautiful country, and remain steadfastly civilised, while the rest of us sink into barbarian unruliness.

Somewhere round the 8 mile point we met the leaders coming back the other way. The first 10 or so runners were elfin Africans, eyes staring straight ahead, mouths almost shut, boney torsos bouncing inside flapping vests, skinny arms slicing through the curtain of rain like it wasn’t there. I marvel at these running machines, though they make me ever more aware of my own imperfections. Let’s face it, I shouldn’t be here. As far as marathons go, I have a body and a demeanour better suited to reclining on a chaise longue, claret glass in hand, watching the race on TV.

But I am here; very much here. Get on with it.

Meilen came sooner than expected. Strangely, I had it in mind that I wouldn’t get there till about 20km, but ping! — it popped up at 16, or just under 10 miles. By now, my pace was just beginning to creep up: 09:52 and 09:56 were 8 and 9. Still nippy by my standards. Just before the turn a loud band of rockers were playing a raunchy “Born To Be Wild”. I gave them a double thumbs up, and they all nodded and smiled. This, and the next minute or two might have been the best moments of the race. 10 miles in, a good chunk of the race behind me, still flying along, and suddenly I’m in the centre of a raucous party.

As we turned right and up through the cobblestoned, picturesque village, there were suddenly hundreds of cheering, applauding, singing spectators waiting to greet us. This was the Zurich Marathon’s Tower Bridge Moment. For a few marvellous seconds I was out of the rain and the cold, and running through a sort of marquee amid a storm of wild

applause and klaxons. What a high these people gave us. This should have been the end of the race. It would have been a handsome 10 mile PB too.

Still buzzing, we quickly rejoined chilly reality and dropped back down into the village to start the long pull home. The prospect of doing it all again, plus another 6 miles, was daunting, yet there’s always some emotional boost when you turn round and start back. We were still 3 miles from halfway, but if I sort of squinted into the rain and didn’t

think too hard, I could almost imagine that we’d got the worst of the race out of the way.

How wrong I was.

On the way back, I saw something that made me both chortle and want to cry out with anxiety. Coming towards me, still on the outward leg, was one wet and bedraggled plump lady, plodding through the rain, her face filled with fear and pain. But it was what came immediately behind her that caught my attention. It was a vision I’d tortured myself with over the past few weeks, like a sleepless child trying to block out the face of the monster, succeeding only in recreating it. It was the sweeper bus, ready to pounce. I saw the face of the driver. Was he really smiling? Oh god. Perhaps some invisible colleague had just said something funny. Or perhaps he had a mean streak, and was eyeing the overweight backside of his first victim of the day. I tried to work out how far behind me they were. Probably at least 20 minutes. Perhaps even 30.

The miles were starting to grow longer. I still felt OK, but the sub-10 miles were now gone for good. 10 to 13 were: 10:17, 10:14, 10:33 and 10:28. This took me up to the halfway point. I looked at my watch as I crossed that magic line. I had to chuckle. 2 hours 10 minutes gave me my third notional PB of the day. I’d run 10K, 10 miles and the half

marathon faster than I’d ever managed before, but I still had another half marathon to go.

Around this point, I had to start admitting to myself that things were getting noticeably harder. Just before Km 23, something significant happened. As I approached the water station, I became aware of some terrible presence behind me. It immediately brought to mind those words from The Ancient Mariner:

Like one that on a lonesome road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turned round, walks on,

And turns no more his head.

Because he knows a fearful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

It was as if some great bird of prey was swooping from behind, ready to snatch me in its talons and carry me off to some desolate eyrie.

The noise got suddenly louder, and they were upon me. It was the 4:29 pacing group, 40 or 50 of them, enveloping me like a toxic cloud. They didn’t know their own strength, and nor did they care. I was pushed out of the way and almost missed the water station as this damp human barrier appeared between us. I had to stop dead to let them pass so that I could reach over and grab another half banana and bottle of water from the final table.

For a moment or two I wondered about trying to cling to their coat-tails. Perhaps they could painlessly sweep me home, like some magic carpet. But this idea was dropped shortly afterwards, along with my bottle, and within a minute or two they’d disappeared round a distant bend.

This was a big moment in the race, and the start of a frustrating period. The sub-11 pace was finished for good. Miles 14 – 17 were 11:09, 11:12, 11:42, 11:38. I still didn’t feel too bad, but the evidence of the watch was inescapable. This was it, and I knew it. The start of a long, uncomfortable run-in. More than a run-in. A bare-knuckled scrap. I hadn’t yet started to flounder, but I knew that being overtaken by the 4:29 juggernaut had lost me some momentum. Chess players talk about “tempo”; an indefinable advantage over your opponent. I’d had the tempo for the first half of the race. Then came a few miles when it was even. But now, 25 km and upwards, I was chasing it.

The villages came and went again, but more slowly and less optimistically than the first time around. We reached Kusnacht. I remembered the words of the tour guide as we’d driven through it the day before: “This is a much sought-after location because of the views and the security. Kusnacht has been the temporary home of Winston Churchill, the Kennedys, the Clintons, and the Backstreet Boys.” Wow. But there was more. It was also home to Thomas Mann and Jung, and is still the location of the Jung Institute of Experimental Psychology. Plenty of raw material here, I thought, as eight thousand dreamers splashed past.

Disappointingly, the big Kusnacht celebrity was nowhere to be seen. Tina Turner, it seems, lives in a mansion down at the water’s edge. River deep, mountain high. But it was a lyric of one of her contemporaries, Gloria Gaynor that seemed more appropriate at this moment. I Will Survive wasn’t written for marathon runners, but it was starting to become my unspoken mantra.

Around Mile 18 I stopped for another pee, in the hope that I really would be arrested and removed. What a tremendous excuse that would be. As I stood there, behind some huge exotic bush, I was aware that my legs were sort of hot and vibrating. It wasn’t an unpleasant sensation but I couldn’t help feeling it wasn’t a great sign. The shoulder was still aching too, though it was an inconvenience rather than a real worry.

A point comes in a marathon when, metaphorically, you have to shut your eyes and empty your head of negative thoughts. You turn up the resilience a few notches and move into auto-pilot. That’s what happened during Km 28-30, which took us to the fringe of the city. 30 was another big landmark. Deliberately miscalculating, I told myself that I

had just another 10km to go. 6 or 7 miles. An easy distance for me.

I saw a highway of diamonds with nobody on it.

We were now back in the city. Zurich on a wet Sunday isn’t much fun. The shops are closed, the streets empty. The trams had been diverted but we could hear them clanging disconsolately in the distance, like a distant rumour of a rival civilisation.

I wanted these city miles to be a triumphal re-entry; a sense that we were returning home, and on the very edge of the finish. But I knew the truth, that we were yet to run a serpentine 6 miles in and around the Zentrum,

I wanted these city miles to be a triumphal re-entry; a sense that we were returning home, and on the very edge of the finish. But I knew the truth, that we were yet to run a serpentine 6 miles in and around the Zentrum,

up and down, backwards and forwards, chasing our tails, plodding ever onwards across rain-washed cobbles, forever catching sight of another part of the field at the far end of the passing streets. Had I been there already? Or was it a stretch yet to come? I lost track. We were in a maze. Were we going around in a big circle? Was someone playing a trick on us? 31, 32 km. Hadn’t I already been past 32 km? Momentary panic. Shoulder hurting.

We were like some rag-tag army, shuffling along, trying to get back to base before the enemy caught up with us. A bunch of drenched rats, seeking warmth and safety. Did I really run all those 9-minute-something miles back at the start? Long gone now. Long gone.

Now they were 12:10, 12:24, 12:38, 12:45, 12:52. The enemy in question was time of course, and that 5 hour cut-off. This was no notional, theoretical opponent. It was real. There, look. There it was again. The

menacingly silent, cream and red sweeper bus was my nemesis. It was the hunter, and I was the hunted. When I first saw it I had maybe 30 minutes over it. Now, in these last few painful miles, the margin had halved. It was coming towards me, up a long street that I’d travelled along just minutes before.

This was the fabled wall alright, and at last, we had finally collided. I’m not sure that I’ve ever experienced this level of discomfort before in a race. Something remarkable struck me. Apart from my 2 pee stops, I hadn’t walked a single step. Unprecedented. Fear had kept me moving. It daunted me at first, but then it did the opposite. It gave me a boost.

I’d been overtaken by many runners in the past 10 miles or so, but now I was passing walkers. Dozens of them. They were walking and I was running. Perhaps shuffling rather than running, but it felt like running, and it made me feel good. I wasn’t going to walk now. I knew that if I stopped for a walk break, that would be it. I’d never get going again.

At 33 km I caught up with another, semi-walking, English woman. She was in a bad way. Maybe it was the rain on her face, but she looked like she’d been crying. She said something to me and I jogged alongside her for a minute or so. “We will do it, won’t we?”, she asked. Her voice was croaky with fatigue. It reminded me that there were probably many

others out there, battling with the cut-off and the bus with the smiling driver. “Stick with me and I’ll get you home”, I said. It brought tears to my eyes to hear myself say this, just as it brought tears to my eyes again to write it. There’s nothing quite like a marathon to whittle away the inhibitions that even alcohol can’t reach. We were lost souls, stateless, friendless, useless. But in one of those marathon moments that will never leave you, we briefly found some

support when we needed it. “Carry on”, she said. “I won’t let you out of my sight”.

I thought about staying with her, but I’d discovered some selfishness during the last part of this race. I’d picked up just a touch of ruthlessness. I would help her, of course, but on my terms. I’d keep going and keep going, and I’d finish in time. She had to keep with me. And the truth is, I never once looked back to see if she was still there.

I also passed a very tall, black guy who was limping so severely that he could barely walk. I mention his colour because it was allowed me to see his leg injury. He’d pulled a muscle so badly that I could see a lump sticking out of his calf. He was wincing and cursing softly in an American accent. He had zero chance of getting back in time. I could see him being gobbled up by the bus in just a few minutes time. Every kilometre from 33 till the end, I had to tell myself to just get to the next distance marker, and everything would be alright. “You’ve come too far not to do it now”.

I could hear myself say those words — to myself — just as I’d said them to the tearful English woman. “Just keep shuffling mate, just keep shuffling and you’ll get there”. And that’s what I did. One foot in front of another. Never stopping, never looking back at that fearful fiend that doth close behind me tread.

Just before 39 kilometres, as I reached a cobbled bridge over the river, I saw a male runner lying in the gutter while a concerned bystander held his hand. I didn’t stop. I could hear an ambulance right behind me, and knew he would be better in their care than mine. I didn’t see the ambulance; that would have meant turning

Just before 39 kilometres, as I reached a cobbled bridge over the river, I saw a male runner lying in the gutter while a concerned bystander held his hand. I didn’t stop. I could hear an ambulance right behind me, and knew he would be better in their care than mine. I didn’t see the ambulance; that would have meant turning

round, and I wasn’t going to turn round. It was only when I saw the race photos later, that I saw the vehicle stopped behind me.

What is this big feeling? Imagine having some rodent inside you, slowly chewing at your entrails. Can you get home before you feel that fatal mouthful? And yet the feeling isn’t as simple and as comprehensible as pain. It doesn’t quite describe the sensation. It’s a bone-deep fatigue; a breathless frustration that my legs are moving without me getting anywhere. It’s like some great physical burden to be carried; a burden that gets heavier with each passing mile. The burden is my own body – the thing that I rely on is now that which holds me back. This stretch of the marathon is where the great paradox begins to reveal itself, at the interface between the physical and the emotional, where you shrink to some blob, half man, half rumour.

The paradox is that the more of those miles that get checked off, the less hope you seem to have of getting to the end. Illusory of course, but you really do believe that everything and nothing is now possible. One thing I promised myself during this bleak period was that this would be my last marathon. I can’t do this again. I won’t do this again. The 35 mile Two Oceans Ultra-Marathon next year? Stuff it. If I can just get round in sub-5, I’ll reward myself by bringing down the curtain on this inglorious marathon career.

But incredibly, those kilometres did, eventually, start to lead somewhere. I don’t recall how, but I was suddenly aware that I’d reached 39 kilometres, and my watch said 4 hours 30. I had half an hour to cover just 3 kilometres. This was the very first point in the race that I knew for sure I had a great chance of getting home in front of the bus. A great chance? 3 kilometres in 30 minutes? It sounds like a breeze, but nothing at this point is a breeze. (Except perhaps a breeze….)

40 kilometres. The final water station. The rain kept coming down, and the shoulder still ached. Everything was the same. We turned another corner, then another, and now we were leaving the city loops and heading for the lake road. More than that, we were heading for the finish. Just keep shuffling and you’ll get there. I kept shuffling. 41 km. I was going to do it. One kilometre left, 12 minutes left to burn before the five hour mark. One foot in front another. Passing more walkers. Round another bend and there it was. The inflated arch across the road in the distance. The finish. I shuffled towards it for 5 minutes without it seeming to get any bigger. Then suddenly it did. I could hear people clapping; I could hear the PA announcing names to a soundtrack of polite cheering. The barriers. Beaming people, cowering under umbrellas. I can see the maroon chip mat just ahead. Shuffle shuffle. I heard my name being announced; I heard the chip bleeping beneath my feet. Was this the end? I kept plodding forward, needing to be sure this was it.

There were people all over the course now. And stationary runners. This was it. I looked at my watch. 4:56. I started to sob.

For the first time in 5 hours, I stopped to walk. It was an unfamiliar sensation. I meandered over to a group of three small, plump middle-aged ladies. One put a medal over my head, and I hugged her. She was confused, but giggled.

Collected teeshirt. No goody bag, but I wasn’t concerned. I had the medal and the teeshirt, and nothing else mattered.

A bunch of random conversations. Incredibly, as I stood at a water stall, glugging for England, I looked to my right and saw the tall American guy who’d had the bad leg injury six miles back. “I think I made it”, he said. We chatted. I gushed about his bravery. Another American appeared. Alaskan. Not met too many of them. Collected my bag. What a relief to put on a fleece. Walking back to the hotel. Still bloody raining. I started to chat to a German guy. He anxiously asked

about Jens Lehman. I gave him the reassurance he wanted. Yes, he’s had a great season, I told him. He’ll be well prepared for the World Cup.

Soon I was lost. My map had disintegrated on the outward journey. I was cold, wet and disorientated, and couldn’t work out where I was. So I did what you do in Zurich, and jumped on a tram. I can’t tell you how good it was to sit on a warm, dry, comfortable tram and watch the succulent department stores on Bahnhofstrasse creep by outside. I didn’t care where I was or where I was going. I was safe at last. I wondered again how Sweder had done in Paris. I knew he’d be OK. Eventually, I arrived at a stop in the city centre where I saw my local tram listed; the one to get me back to the hotel. I clambered off here and straight onto the number 10.

Soon I was lost. My map had disintegrated on the outward journey. I was cold, wet and disorientated, and couldn’t work out where I was. So I did what you do in Zurich, and jumped on a tram. I can’t tell you how good it was to sit on a warm, dry, comfortable tram and watch the succulent department stores on Bahnhofstrasse creep by outside. I didn’t care where I was or where I was going. I was safe at last. I wondered again how Sweder had done in Paris. I knew he’d be OK. Eventually, I arrived at a stop in the city centre where I saw my local tram listed; the one to get me back to the hotel. I clambered off here and straight onto the number 10.

In my hotel room, I sat in an armchair for 20 minutes, babbling to M about what I’d seen and done. Admirably, she pretended to be interested. She’d spent the day in bed, her sleep punctuated only by the occasional rush to the bathroom to vomit. Me? I’d run a marathon in the rain. Did I tell you?

First a shower to wash away all that hard-won sweat, then a luxurious soak in the bath for an hour or more. Peace at last. Total tranquility. I could hear nothing but the warm water lapping round my ears. For the first time in hours, my shoulder no longer hurt.

I remembered a conversation with an ex-heroin addict who’d taken up running. He told me that this was exactly like what a shot of the drug was like — sinking back into a warm bath after running a marathon. No more problems; nothing to worry about. Job done, let the pain and stress wash away. I closed my eyes and tried to think about my marathon

morning.

Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son…?

I’ve stumbled on the side of twelve misty mountains,

I’ve walked and I’ve crawled on six crooked highways,

I’ve stepped in the middle of seven sad forests,

I’ve been out in front of a dozen dead oceans,

I’ve been ten thousand miles in the mouth of a graveyard…

And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall.

The first item of clothing on was, of course, the finisher’s tee-shirt. I instructed an exasperated M to take several photos until I got one displaying just the right amount of smugness. Great. This one will go on the website, I thought.

My post-race plan was to find an Irish pub where I could sink a few Guinnesses and watch Manchester United play Arsenal. Tragically, this heavenly scenario was never realised as most of Zurich, I was to discover, shuts down on Sundays. I spent a fruitless 90 minutes trying to find one of the two likely places I’d been told about. Eventually, I did track them both down, but neither was open. It was still raining. Worse, the rain was beginning to turn to sleet. I changed plan and took a tram back to the area of the hotel where I finally found somewhere open, albeit a Darts & Disco Bar.

It did the job. I found a table in the corner, beneath a huge plasma screen showing a documentary on the Beckhams. I ordered a half litre of Hoegaarden Witbier (wheet beer) and a pizza the size of a dustbin lid. A few minutes later, I took out my notebook and wrote: “Why do grey haired, fat old men run marathons?”

I was still staring at that question when my order arrived. Greedily, I stuffed a huge slice of pizza into my mouth and chomped till it was gone. Then I transferred most of the contents of the beer glass to my stomach in one deft movement. I felt truly human for the first time today. More than that. Superhuman.

I looked down at my notebook again. “Why do grey haired, fat old men run marathons?”

I knew the answer.

To arrive at this feeling again. That’s why.