Note:

This entry was created over several weeks. The great bulk was written while in the USA, but I wasn’t happy with it, so I left it to congeal on my local drive. On May 17, I padded it out, and have retained the perspective of this date for the post, even though I have tried to soften its sharper edges since then. And I will almost certainly tinker with it some more. In particular, I have a lot of photographs and pieces of video from the race, and from our subsequent travels, that I need to do something with.

Seventeen days in the USA after the Boston marathon was always going to be risky. I try to avoid clichés like the plague, but “It’s all gone pear-shaped” is as irresistible as cuisine américaine is to the relieved marathon survivor.

Despite my alluring old buddy, good intentions, post-marathon exercise has been minimal. A brief elephantine plod along the seedy main drag of Sherman Oaks, Los Angeles, before returning to a huge peanut butter and chocolate pastry, worth five times the calories expended on the run, pretty much summed up the seriousness of my efforts. Holiday apathy is forgivable while it’s happening, and particularly while bouncing round the south-west of the US, anaesthetised by sunshine and the endless buffet of popular culture. But since arriving back in Blighty, a week ago, the expected cloud of remorse has descended.

Probably just a case of delayed-onset post-marathon blues, though it’s been an annoyingly depressing week, returning to a pedestrian routine after the excitement of Boston, and the anticipation of Boston. The waiting workload seemed mountainous, current goals ill-fitting and futile. More tellingly, I’ve been ill for four days with stomach pains, and sleep has been fitful, which hasn’t improved my mood.

But today at last, I feel better. It’s OK. I’ve been here before, and know what to do. It’s time for a new plan and renewed optimism. But first, there’s some catching up to do.

Four weeks since I posted anything here. Better probably to have despatched small, frequent packets instead of trying to cram this mass of fragments into one neatly wrapped, tightly sealed parcel.

It seems a long time ago now, but a month ago today, almost to the hour, I set off for my last pre-race loosener. It’s often noted that running exposes parts of the world, and of ourselves, not normally seen, and I can be pretty sure that the raw Boston underbelly glimpsed that morning won’t appear on too many visitor itineraries. Our hotel was on the south side of the city, a couple of miles from the centre. Garages, light industrial units and offices, mostly empty or boarded up. And it’s not just the businesses that get abandoned here. People too. I stop at a busy intersection, where one grizzled old man in a torn raincoat, belted with a piece of blue nylon rope, guzzling beer from a can, grins at me. He guesses right, and`bids me good luck in Monday’s race. I thank him, and move on.

I was still hollow from the grinding journey over the Atlantic. My body clock had jangled me awake at 5 a.m., and that was that. For an hour I tried making my head a no-entry zone for the noise of the six lanes of traffic just beyond the hotel window, but eventually I gave up, cut my losses, and slipped out for these 3½ easy miles before breakfast.

A little further on from the prescient vagrant, a driver at a red light called out: “You here for the race?” After my shouted “Yes!”, he turned round, and I heard him say: “Hey kids, it’s a marathon runner!” The rear window descended frantically, and a boy’s face appeared. About 8 or 9 years old. He cried out urgently: “You have to run fast in the race! You know why?” He didn’t wait for an answer. “Because Boston is the best mara-thon in the whole world!”

The dad chuckled proudly. “This town welcomes all marathon runners. Give it your best.” We each brandished a raised thumb, and went on our way.

It was the first evidence of what I’d often heard: that Bostonians are proud of their race in a way that Londoners or New Yorkers aren’t. Not that we are dismissive of our respective marathons, but the race comes and goes without non-runners caring very much. It’s just another annual spot on the calendar. In Boston, it’s a big deal. They are proud of their city’s history, and the race is a piece of that history, stretching back 113 years. In marathon terms, this is an eon; the oldest continuously-run marathon in the world by a very long way. And unlike the Finchley 20, it has been run on an identical course the entire time, with the exception that post 1908, the course was extended to start at Hopkinton rather than Ashland, to fit in with the change in the marathon distance from 25 miles to 26.2. Add in the fact that the great majority of entrants have to run a qualifying time to get in, and the mystique of the event gets inflated yet further.

I’m not one of that elevated qualifying majority. My place arrived courtesy of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. (Please don’t forget to sponsor me — thank you.)

American hotels could maybe teach us a thing or two about showers, but not about breakfast. After sensational niagarablutions, the usual struggle ensued, trying to find something healthy to scavenge from the array of econo-items. It wasn’t going to matter after tomorrow, but I had to make do with unexpectedly sugary bran flakes, and a banana. Oh for a china bowl of Dorset porridge oats, sprinkled with chopped, fresh strawberries, blueberries, sultanas and walnuts, with a smoothie chaser.

On marathon morning, two days later, I awoke to a feast of indecision:

- Feet — Compeeds or Vaseline or surgical tape? Or a combination of two or more? Which would provide most protection against blisters?

- Socks — I’d brought two pairs from home: battle-worn Thorlos and those cheap padded numbers from Aldi. But now I’d over-complicated things by investing in a multi-pack of thin ankle socks from the local Target store.

- Shorts — My skimpy ‘racing shorts’; or the thick, generously lined longsters with the capacious pockets? Or should I finally carry out my threat to wear only my scandalously revealing lycra undershorts? The dangerous consequences of getting that one wrong dangled in my imagination.

- Cap — I admit it. It can’t be a common ailment, but I’ll come clean: I’m addicted to jogging headgear. I’d brought two caps with me, and picked up another two at the expo. Which one would be asked to step up to the pate?

- Shirt — The big one. Should I follow my perceived obligation to the JDRF, and wear their garish Pingu number, even though it did me few favours in the Finchley 20 and Worthing 20? Or should I fly my own flag and opt for the stylish RunningCommentary garment (still available in vest or tee for only £20…). Or would I fall back on the tried-and-tested grey singlet adorned with my name, purchased at the Chicago Marathon expo, and worn in that race, as well as at Copenhagen in 2004 and Hamburg in 2005?

- Gels — Would I stick to the tacky PowerBar? Or adhere to the Hi-5 plan? Or would I come unstuck if I risked one of those exotic potions collected from the expo the day before? I didn’t have a glue.

- Breakfast— Yes or no? And if yes, then when and what and how much?

- Hydration — A good gargle to wet the whistle and lubricate the limbs, but suffer disposal issues? Or stay dry and risk dehydration and catastrophic engine failure?

- Early or late bus — Get to Hopkinton in plenty of time to bag a decent berth in the tent, but risk debilitating boredom and trench foot? Or take one of the later buses, and miss out on the life-affirming camaraderie of the runners?

I woke at 4 a.m., and rolled these dilemmas around in my head, examining each angle carefully, deploying the sort of sound judgment available to us at 4 a.m. In the end, I did what I do in a restaurant when the menu contains so many possibilities that I’m paralysed by choice. When the waitress asks if I’m ready to order, I say yes. In the time it takes her to whip out her notepad, lick a pencil, and raise an expectant eyebrow, I know a decision will come. All I do is to stop thinking about it. At 5.30 a.m. I was up and in the shower, knowing that by the time I reclaimed my place on dry land, and in a position to reach for pedal medicaments, and apparel, and energy aids, all decisions would have been subconsciously made.

Bah! I bet John J McDermott, the 1897 winner, didn’t agonise over these things. After his cold shower in the yard, he’ll have pulled on his cotton shirt and tweed breeches, coarse woollen socks and sturdy hiking shoes, before sitting down to a mountainous fried breakfast. Then out the door to jog miles to the start line.

It makes you wonder, and worry, what the Boston winner of 2109 will be wearing, and what preparations and supplements will be on hand, and what sort of gadgetry will be employed.

Let history know this: I went for Compeeds and Vaseline but not surgical tape, then wrapped those oleaginous feet in Aldi specials; the shorts were long and baggy with voluminous pockets while the cap was old faithful: the canary yellow Hal Higdon special — 6½ years of steadfast service. The JDRF Pingu number won the distinction of concealing the horrors of the world from my beer belly. I would be filling my gut with Hi-5 gloop every 5 miles, but not breakfast. At least, not until Hopkinton, when the fruit bagels and banana and coffee on offer was more than a hungry man could reasonably be expected to resist. A half litre of sports drink would be absorbed on the neither-too-late-nor-too-early bus, and another half litre shortly before the start.

At 6.30, I walked through the hotel lobby, stopping briefly at the public PC to Tweet my anxiety, before stepping into the pale sunshine of a Boston Marathon morning.

This would be my sixth marathon, but the first for 3 years. How had such a gap opened up? Where had I been? I couldn’t recollect what had changed after Zurich in 2006. I had, at last, dipped below five hours in that marathon, and was looking forward to compressing those twenty six miles into a smaller timebox than the still over-capacious four hours and fifty six minutes. And then something must have happened, but I couldn’t think what.

Since 2001, my plan had been to run a marathon, on average, every year. It worked out that way for 5 years. London, Chicago, Copenhagen, Hamburg, Zurich. My running history began to look like the label of a cut-price perfume bottle. In addition to the spring jaunts, every year since Zurich I confidently announced a bonus marathon appearance in autumn — usually Dublin. But something always fell from the sky to derail my ponderous summer journey required to get me there. Illness in 2006; general lethargy in 2007; and in 2008, a puzzling knee inflammation that had me barely able to bend the joint at times late last summer, before correcting itself just as mysteriously, as soon as a specialist was invited to fix it.

Struggling through those final, wind-blown miles at Boston this year, was like emerging from some extended lost weekend. It was hard to absorb the plain fact that I’d not experienced that sense of empty, pointless fatigue for three years. And I couldn’t work out where the time had gone.

This is no heroic tale. How nice it would have been, to report that after my long lay-off, I’d bounced down Boylston Street with a handsome PB in my pocket, wearing a banana-like grin, cap at a jaunty angle, tears of relief racing down my salty cheeks.

But this wasn’t how it was. It was a tough experience: sinewy, elemental and uncompromising. Contrary to hope and expectation, there was no outpouring at the end. No spiritual unravelling. No kneeling at the Boston shrine. No detonation of inspired elation. How tempting, and how easy, to pretend it was the race of my fantasies, and not the other sort. But the hard fact is that it took me five hours and twenty two minutes to cover the Boston hills, and no amount of turd polishing skill will change this inconvenient statistic.

In mitigation, m’lud, injury had revisited for the Boston campaign, this time the left calf coming under attack. Two separate strains drove several running weeks from the schedule, though I was saved by long, tedious sessions in the gym, where I could notch up the required cardio-vascular hours without putting too much stress on the lower limbs. So looking at the experience through those lenses, I was delighted to have finished without yanking my calf, and without any great hangover of physical pain beyond the expected fatigue that comes with a 26 mile hilly plod.

I first became aware of this great race in the middle of 2001 when, as a rookie runner, I started peering into the old Hal Higdon web forum. There was much esoteric discussion about BQ-ing, which at first I took as a reference to shopping for DIY materials. But the fog soon cleared, and I learnt that a BQ was a Boston qualification, and that it represented the holy grail of the sport for the average Joe Runner. The mystique of this event grew with each anecdote. Places with pedestrian names like Wellesley College and Hopkinton and Kenmore Square and Boylston Street, began to acquire a rarefied status that soon had them hovering above the ordinary chap’s planet earth in their own dimension. Added to this list were reference points with more compelling names: the Scream Tunnel, Newton Lower Falls, the fire station turn, the Framingham railroad, the Johnny Kelly statue, the Citgo sign, and perhaps most potent of all, Heartbreak Hill.

Even now, after 8 years of plodding and reading and taking an interest, excluding events I’ve taken part in myself, I can barely think of a single well-known landmark in any other race. [Wrinkles nose; thinks.] Maybe the final bit of the New York Marathon, through Central Park, or Chapman’s Peak in South Africa’s Two Oceans marathon, or… Or?

I admit that I thought taking part in this great event would represent some final, epic act of consummation that would have me in thrall from start to finish. But that’s not how it was. Once I was underway, the mystical fluff was blasted away by the practical challenge of surviving the 26 mile grind. The only serious emotional wobble came after a kink in the long Beacon Street drag, beyond which the Citgo sign suddenly came into view. Twenty five miles in, the emotions are fragile. And here I was, at last, face to face with a symbol that’s been my animated screensaver for the past six months.

It’s famous because it’s precisely one mile to the finish line. Before that moment, all I could see and know was the blankness of a marathon’s end: that peculiar sensation of non-existence; a life from which all colour and all sweetness has been sucked. And here, unexpectedly, folded into that weird other-world, and suddenly revealed, is that gaudy, illuminated landmark that becomes an existential lifeline. Its message is simple: Almost home.

Six thirty a.m. now seemed like a very long time ago. It was only 9 hours earlier, but seemed to belong in some other pocket of time; some other galaxy.

At 6.30 I’d been striding over the sleep-thieving Highway 93 to Andrew, the grubby local T station, following the band of brothers with their fluorescent yellow, drawstrung plastic gear bags. This brief journey up to Park Street station reminded me of London in 2002, when the early-morning tube was filled with anxious trainer-wearers similarly bearing identikit marathon bags. The difference in Boston was the number of… civilians travelling. I didn’t get a seat until nearly time to get off. Why are so many non-runners travelling into the city centre at 6:30 am on a public holiday? I’d asked myself the same question on the bridge over the highway. So much traffic. Why? These people should be still snoring in their beds, stinking of cheap whisky.

Despite the population density, the atmosphere on the journey was muted and pensive. This was all about to change. The train uncorked us at Boston Common, the lungs of the city, where twenty thousand people jostled good-naturedly to board one of the endless stream of canary-yellow, beautifully retro school buses. The atmosphere was bustling but not chaotic, excited rather than apprehensive. I tip my cap to the MIT students responsible for herding us on, entertaining us, and keeping our spirits buoyant. One of the yellow-clad student marshals, behaving as if he was casually chatting to a friend over a coffee, explained to the world through his megaphone: “Look, no disrespect to our neighbours from Harvard Square, or to any graduates here, but frankly, those Harvard guys suck. They don’t party, they won’t party. Hell, they can’t party.”

Against a backdrop of these random observations on Boston life, we inched closer to the kerb. I remember issuing an involuntary, loud exhalation as I climbed aboard, as if I was saying: “This is it. No going back now.” I found a seat at the back, and took a look around. People were smiling and nodding to each other. Most of my fellow travellers appeared to be race-worn veterans, many flaunting the insignia of Bostons past, like old soldiers proudly bearing their campaign ribbons. Every year has its own design and colour scheme, and after a day in the city, you can see at a glance who was here last year, or earlier. Some like to emphasise their athletic longevity by displaying a fashion mess stretching back a couple of decades. In particular, I noticed the 1994 vets. The Boston jacket for that year, with its broad blue and white hooped design, could easily have doubled for QPR apparel.

Glancing over at my neighbours on the adjacent double seat, I witness different attitudes. One, an angular, hunched, intense man with a gimlet eye, is squinting into an invisible patch of territory, like a hunter waiting for his quarry to make a move. His bony fingers rhythmically crush a bright orange stress ball. Next to him, his companion is leaning back with eyes shut, a distant smirk on his face. His cap, pulled down over his face, carries the slogan: 26.2: the destination is the reward. Something tells me that both men have been here before, but have arrived via different paths.

This snapshot of contiguous diversity brought back a broader experience from the previous day. It’s a strange thing, but (at this admittedly early point) my strongest memory from Boston happened not in the race itself, but the previous day, in a small sideroom at the expo in the Hynes Convention Centre, close to the finish line.

I very nearly missed the session. Certainly the great majority of runners did. There weren’t many of us in there to see it, perhaps a couple of hundred, but up there on the platform were five American heroes, each having added a layer to the myth of Boston. What a privilege to listen to these people and to their stories. Each spoke off-the-cuff for 10 or 15 minutes. Five voices, five tales. In the main, they spoke directly and confidently, with wit and charm and eloquence. But each had faltering moments, in which they showed a touching humility and respect for the race and for anyone who was yet to experience it.

The aristocratic looking Amby Burfoot kicked off. Executive Editor at Runner’s World magazine (the US version) these days, but in a former life, top athlete and winner of Boston in 1968. To a hushed room, he talks about miles ten to twenty in that victorious race, when he was just ahead of his rival throughout. Every step of those ten miles, he could see the shadow alongside his own, without ever seeing the man. Each time he thought he must have wriggled free, he looked down to see the same ominous shadow chasing his own. Up Heartbreak Hill and down the other side, the shadow still there, just behind him. Through the infamous Cemetery Mile that follows Heartbreak. And then, at last, at the end of that stretch, he looks down and the shadow is gone. It allows him to power forward with five miles to go, and he takes the laurel wreath. The lesson of his story is the value of tenacity and self-belief.

Eyebrow-winching aside: Burfoot also mentioned that in those days, there was no water available for runners on the course. Aid stations every couple of miles are a relatively recent introduction.

Next up is Jack Fultz, the gregarious and amiable 1976 winner. It was the hottest Boston on record, when temperatures exceeded 100 degrees. Fultz is now a sports psychologist and natural entertainer. On the notorious downhill start of the race: “If you don’t think you’re going too slow during those first few miles, then you’re going too fast.” And another Fultzism: “The longest distance in the marathon is the 6 inches between our ears. Winning our own mental race is almost always tougher than winning the physical one.”

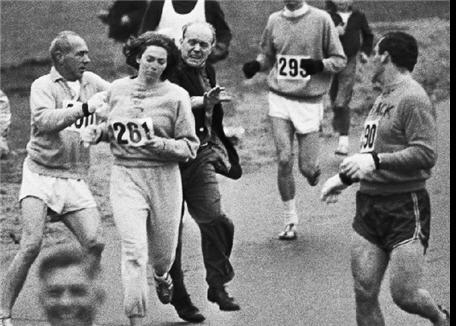

1967, a year that fascinates me. Kathy Switzer would change Boston history by being the first woman to complete the race. It was still a men-only event when she clandestinely entered, and was unwittingly accepted, under the gender-neutral name of KV Switzer. A few miles into the race, word spread via the press boys to the race director, Jock Semple, that there was a girl out there on the course. Astonished and horrified, he located the guilty party and tried to drag her off the road. With the help of fellow runners, Switzer was able to escape Semple’s aggression, and went on to finish in a creditable 4:20.

The photographs are many and famous, and to Semple’s embarrassment, made the front pages of newspapers around the world the following day. Reluctantly, he had to concede that perhaps it really was possible for women to run 26 miles, a claim he had previously denied. It was an ungracious, reluctant climb-down, and it’s unlikely he ever made it to Germaine Greer’s Christmas card list. But the rules were duly changed, and women’s marathon running became established. It doesn’t matter that had Kathy Switzer not done it, someone else would. She stepped up first, eventually becoming a 2:50 Bostonian, and a well known TV journalist. She deserves her reputation as a sort of patron saint of women’s running. As she took us through the events of the day, and detailed the confrontation and its aftermath, the woman next to me dabbed her eyes as if to acknowledge some sort of debt to the woman standing in front of us.

And incidentally, she’s as elegant now as she was then. Almost. Perhaps at my age, I’m a little more flexible in these matters than I once was.

The fourth member of the panel was Greg Meyer, who won Boston in 2:09 in 1983, the last American to do so. He made me laugh out loud several times, but I’m sorry to report that I can’t recall much else about him. I must have been still intoxicated by the Switzer tale. Sorry Greg.

Finally, we had Dick Beardsley, of Duel in the Sun fame. Joint winner of the inaugural London marathon in 1981 (an event I spectated at), and still the 3rd fastest US marathoner in history, in 1982 he took part in the most keenly contested Boston marathon of them all. He kept up with the favourite, Alberto Salazar, stride for stride the entire race. “We ran that first mile in four minutes thirty three”, he explained, “And after that, I was hanging on. Let me tell you: when you feel yourself hanging on with more than twenty five miles still to go, then you know you’re in trouble. It was a marathon that came down to a final one hundred yard sprint.” He paused. “I lost the race by 1.6 seconds”.

One painful subject not mentioned by Beardsley, unsurprisingly, was that he later suffered a nasty industrial accident on his farm, and then a bad car crash. His injuries led to him becoming dependent on strong pain killing drugs. He began forging prescriptions to satisfy his habit, and eventually spiralled into chronic methadone addiction and attention from the police. He’s now clean, but he still offers the world a vulnerable, haunted persona.

Five different runners; five different stories to tell. I thought I’d done my research into the race, boning up on the theory, with the practical test still to come, but here was a new and unexpected level of experience. I left that room with a greater sense of what Boston means. I’d had trouble locating it, and had considered not bothering, but how glad I was to have made the effort. Even now, weeks later, it’s my sharpest memory of the weekend.

The centrepiece of the ‘athletes village’ at Hopkinton is a huge marquee with no sides. Between the snaking queues for what we would call portaloos, but what the Americans call portajohns, or even more grinningly, portapotties, runners wrapped in blankets and plastic sheets lie on the ground. It’s like a field hospital in a scene from the American civil war. The wind whips through it, dragging from you the excitement generated by the bus ride. I wonder why I am here, when others are in their beds, dead to the world, and dead to the anxieties of the long road ahead.

This was a strange period when I seemed to lose all interest in the event. I seemed not to care. I break a rule by drinking coffee and sports drink, and eating fruit bagels and a cereal bar. It’s unheard of for me to ingest so much so soon before a race. But I am hungry and bored and scared, and need something to comfort me.

A is for apple; the main ingredient of the pies mom makes in Hopkinton. This was how I saw it. A nice, old-fashioned, middle-class, small town in Massachusetts. White wooden houses with the American flag fluttering in the small front yard. God-fearing residents with gleaming teeth, already applauding us, though we were doing nothing braver than walking to the start line.

Down to main street and left to find my corral — number 24. It was a marathon start like no other I’ve seen. This was more like a small town 10K, but with 25,000 entrants. Enthusiastic crowds lined the grassy banks and cheered. Kids hopped up and down, waving paper flags.

This was it. I’d read so many reviews, and at last I was getting to see the movie.

And then the gun, and like some mass jail-break, we are flooding down the hill to freedom under the grin of a fragile New England sun. Oh how good life seems in that first shining mile or two. I am so intoxicated by the realisation that here I am at last, enjoying the moment I’d wondered about for years, that for the first time ever, I forget to turn my watch on until half a mile down that first wooded hill.

Coming into Ashland at mile 2, I see the famous TJ’s Diner to my left, and as expected, the gang of leather=clad bikers dancing on the tables set up along the roadside. They wave their beer cans and jig to the strains of some undistinguished heavy metal. They are just one more stage direction among many in the script for the annual show.

And so it goes on, with Ashland dribbling on for miles, the way that American towns do, before seeping into Framingham on about 6 miles. I felt the way I was told I should feel — as though I was going way too slowly. Surely I could have been hammering along here at least two minutes a mile faster? And I could have been, but everything I’d read and heard and been warned about told me to fight my instincts, and creep along at a tentative pace. I’ve since wondered if I shouldn’t have just ‘done a Zurich’ and just gone for it from the start. Hindsight is twenty-twenty of course, and anyway, I have to remind myself that running a stupid race could have stirred the calf.

The running landscape through these early miles remains the same mixture of residential streets, garages, cheap eateries and stretches of pleasant woodland — handy for bladder-emptying dashes. I have two of these.

Approaching Framingham, I cross the famous railroad tracks. In 1907, the leading pack of 10 runners got across just before the long freight train hauled itself through the town, effectively consigning the rest of the field to also-rans. From that year onwards, the trains were suspended until all runners had crossed.

Running through Framingham, I reminded myself of a surprising fact — that I nearly became a resident of this town. Had things turned out a little different, I might have been standing there, cheering, beer in hand. Ten years ago, I worked for a company who asked me if I wanted to do a 2-year stint at their office in Boston. Yes, why not? Someone suggested Framingham as a good town to rent a house, and we started researching our options. I even spoke to a couple of lettings agencies, and made enquiries about M getting a teaching job. And then, quite unexpectedly, the division I worked in announced worse-than-expected sales figures, and the decision was made to close us down. I never made it to Boston, and found myself redundant instead. Plodding through the strung-out town was like finally visiting a place I’d once had a dream about.

I was buoyant for the first 10 or 11 miles, as the road trickled through beaming, middle-class America. They waved their flags and called my name like I was their son or brother or father. There is nothing bad to say about these people. It’s their day as well as ours. For many of the runners, a one-off; for them, an annual holiday to celebrate their communities and their very existence. They enjoy the knowledge that this famous old race elevates their towns into something beyond their natural significance. I wondered if these places were really there on the other 364 days of the year, or were they just a set-dressing task facing the organisers in the days leading up to the race?

By mile 12 I was tiring, and had to stop to whip off my left shoe and sock. It felt like one of my anti-blister Compeeds had slipped off. This is a danger signal, and needs attention. If ignored, the loose plaster will rub off your flesh, and you’ll end the race with a shoeful of blood, and a wound that will take days to start healing. But no, sitting there at the side of the road, with 3 open-mouthed kids staring down at my blackened toes, everything seemed in order.

The pit-stop had taken no more than a minute, but strangely, it was a turning point in the race. Something seemed to get left behind on the streets of Natick. Where had all my energy gone?

A brief respite came a mile or so later, when I gradually became aware of some eerie, high-pitched sound. For a while it came and went with the gusting wind. It would have been tempting to think I was imagining it, but I’d been expecting it, and knew precisely what it meant. Here I was, at long last, approaching Wellesley, and about to experience the long plod past the banshee hysteria of the girls’ college. Hillary Clinton was a student here, and I wondered if she too had taken part in this famous annual ritual, where the streets are lined with screaming women for the two hours or so that the race passes. I was surprised at how few of them were. Like the English longbowmen at Agincourt, their achievements greatly outweighed their numbers.

A brief respite came a mile or so later, when I gradually became aware of some eerie, high-pitched sound. For a while it came and went with the gusting wind. It would have been tempting to think I was imagining it, but I’d been expecting it, and knew precisely what it meant. Here I was, at long last, approaching Wellesley, and about to experience the long plod past the banshee hysteria of the girls’ college. Hillary Clinton was a student here, and I wondered if she too had taken part in this famous annual ritual, where the streets are lined with screaming women for the two hours or so that the race passes. I was surprised at how few of them were. Like the English longbowmen at Agincourt, their achievements greatly outweighed their numbers.

The ‘scream tunnel’ was a tremendous highlight of the Boston experience, and some of the signs waved by the girls brought a broad grin and a little bounciness to this flagging middle-aged carcass. I managed to grab some video as I sauntered past, but this screenshot will give you an idea of the torment we were subjected to.

My spirits had been hoisted, and I thank the Wellesley shriekers for the helping hand. It happened at a good time, though sadly, the effects didn’t last. A couple of miles along the road, I was feeling flat again. The road, unfortunately, was anything but. After a first half of gentle undulations, mainly downwards, we started to hit the hills — at just the wrong time.

The first 16 miles of Boston is a straight line, but then we arrive in Newton Lower Falls, winding towards the famous fire station turn, a sudden, and disorientating, 90 degree switch. I wanted to feel a thrill as I passed this celebrated landmark, but it wouldn’t come. Instead, all I could see, stretching up ahead of me, was the first of the 4 hills that make Boston Boston. Curiously, these legendary hills are not particularly steep, nor is any of them longer than half a mile. It’s not their magnitude, but where they come in the race that makes them fearsome. At 16½ miles, the fatigue has started to drain your morale. You’re starting to feel defeated, yet there are still 10 miles to get through. Even though their bark is worse than their bite, the very sight of those hills is a merciless twist of the marathon blade.

Some days later, as I sat on a sunny hotel balcony in Las Vegas, silent glass of rich, viscous Californian chardonnay in hand, I tried to make some notes about those final ten miles of the Boston marathon. I’m looking at the page now. There’s a scattering of pedestrian phrases but nothing insightful. The final stretch of any marathon is about an absence of things in any case, so perhaps the almost-blank page sums it up quite well.

The Newton hills dragged on like some gargantuan slow-motion roller-coaster, where the thrills belonged to the spectators and not the participants. As for Heartbreak Hill, I missed it. It was only as I shuffled past Boston College that I realised I must have got past the crest. How does it get its name? I’ll let Wikipedia do my work for me here:

The nickname “Heartbreak Hill” originated with an event in the 1936 race. On this stretch, defending champion John A. Kelley caught race leader Ellison “Tarzan” Brown, giving Brown a consolatory pat on the shoulder as he passed. His competitive drive apparently stoked by this gesture, Tarzan Brown rallied, pulled away from Kelley, and went on to win—in the words of Boston Globe reporter Jerry Nason, “breaking Kelley’s heart.”

From that day on, it was Heartbreak Hill.

The kids at Boston College were every bit as lusty and as enthusiastic as their Wellesley rivals, though perhaps I was less appreciative of their efforts. Again, I snatched some video which I’ll post soon. It was the final piece of video I took. Just after Heartbreak Hill, my batteries went dead. How very appropriate.

Also appropriate is Cemetery Mile that follows Heartbreak. I was tempted to take my place with the deceased, but I knew I’d never get over that wall. In any case, I had a more important wall to deal with. I knew I was now glycogen-depleted, and no carbohydrate intake seemed to be restoring it. The old cliché, that the 20 mile mark is the half way point of a marathon, was never more vividly illustrated than it was this year in Boston.

It was at least good to see mile markers in the 20s, which starts to offer some faint promise of an end to all this. This is also the start of the long straight road, Beacon Street, into the heart of the city. It was survival shuffle through this extended stretch. The hills were gone, but so was I. Every time I stopped to walk, people would yell my name and urge me on, and I’d find some extra half-notch of effort, even though I’m not at all sure I was going any faster than had I been casually strolling. On we plod, eyes blank, mouths open, our grim faces the colour of boiled ham.

The physiological paragraph. It was my glutes that did for me. 16 miles of constant undulation wrecked them. By the time I got to Newton, every step was sending a crackle of pain up my thighs, into my backside and on up my spine. I expected my legs to ache — that happens in any long run. But normally that’s where the pain stops. This time, the slopes had attacked the glutes (the muscles in my backside), and weakened my whole body. It was no surprise. The earlier calf trouble I’d had in my training had ruled out any hill running, which everyone told me is essential for Boston preparation. But I have to remind myself that there was a period when I thought that I would never get this far. I trained to be able to get to the start line. After that I was on my own.

At least I was lucky with the weather. The day had started brightly, with the threat of heat, but it never happened. Instead, we had a cool, blustery day in which discarded paper cups and spent gel wrappers danced around my ankles, mocking my efforts. There was an aid station every mile dispensing water, Gatorade, and more encouragement than one man really deserved. If the lack of sunshine was a boost in one way, it worked against me in another. It made those final, awful 5 miles vividly grey and featureless. Listless, cheerless, colourless, anaemic. I think this is why I see a blank page in my notes. There is nothing there because… because there was nothing there. Everything I had ever been or hoped for had been tipped out of me. It’s here I always urge myself: “Next time, get properly fit.”

Brookline. Cleveland Circle, Coolidge Corner, and finally, there in the distance, the blessed Citgo sign, and one mile to go. The agony of the landmark is that you see it a long time before you get to it. Like seeing the tiger in the Sundarbans of Bangladesh. If you stick at it long enough, you’ll find it. And my god, there it was, alongside Fenway Park, legendary home of the Boston Red Sox.

Kenmore Square, Commonwealth Avenue. The right turn into Hereford Street, where you’re shocked to find another small incline to struggle up. And then, up ahead, a T-junction where you swing left, beneath one of the most famous street signs in the marasphere: Boyleston Street.

Again, I should have been elated. I should have been laughing and hurling my cap in the air. That’s how my reveries had scripted the journey. Instead, I felt small and insignificant. I wasn’t a person or even a piece of litter blowing along the gutter. The lights had gone out. I was just a fleck of dust; a disembodied statistic.

In the far distance I could see the finish line, but it didn’t seem to excite me. What did finally pump some colour back into me was seeing M, squealing at the side of the road. “I’ve been waiting an hour and a half,” she screamed tetchily. “Where the hell have you been?”

It was an excellent question. Where the hell had I been? I had no answer. We hugged and laughed. “See you in a minute.”

How good, just then, to have seen something familiar and of my world. It yanked me out of my hole, and at least meant that I could cross the line with a smile on my face.

A half hour later, medal dangling from my neck, I sank my teeth into the biggest hamburger on the menu at B.Good in Dartmouth Street. We’d tried getting into Clery’s, where I’d arranged to meet some other Brits from the Runner’s World forum, but by the time I’d struggled over the finish line, the bar had filled up, and there was a long queue outside. Food was an even better idea than a pint of Guinness.

The beer came the next day, when I sat in a deserted Irish bar, where I’d been deposited by M. We’d done the tourist walk around the city: the Freedom Trail, following the red stones in the pavement to view some of Boston’s many historic buildings and locations. Walking is a great post-marathon activity, though beer is an even better one. While M went off to shop, I finally allowed myself the luxury of a post-Boston beer.

As I sat there in that quiet space, luxuriating in Guinness (albeit the foreign stuff which is never as good), making a few notes, reading the race report in the Globe, someone came in and had a word with the barman. A few seconds later, the giant TV screen flickered on, and there was Liverpool playing Arsenal. I was confused: was this a re-run? But then I worked out the time difference, and realised this must be a live game. What joy. And it finished 4-4, in one of the most exciting matches of the season. Three or four beers, some banter with a Port Vale fan, and a 4-4, followed by a trip to Fenway Park to see the Red Sox demolish the Minnesota Twins. A great day, apart from the nagging sense of anticlimax about the race. This is something I continue to wonder about.

Five days in Boston, followed by five in Las Vegas.

Vegas is an outrageous city. I was a Vegas virgin, and quickly grew tired of it. Loved the set, hated the cast. I sense that the only way of dealing with the place is to go in on its own low level, with a bunch of mates and a combustible stack of cash. Without these items, I couldn’t psyche myself up for it. Or couldn’t sustain the initial excitement. Instead, I found it insufferably low-rent, full of drunken English kids tottering round the casinos, glugging cocktails, hoping to look the part, but not getting close to pulling it off. And a variety of other unappealing types; grim-faced losers in the main. There was something corrupt and dissolute and tacky and phoney about the Las Vegas micro-society that bored and depressed me very rapidly. I coped with it by spending as much time as possible relaxing in our superb, and inexpensive, hotel suite at the Staybridge. How pleasant to experience an absence of anxiety about anything beyond Premier League relegation issues. It seemed like a long time since I’d enjoyed that simple pleasure.

If humans are excluded, there is much to like about Las Vegas. There’s humour and humanity in well-executed kitsch, and this city surely has more top-hole kitsch than any other in the world. And then there was Love, the Cirque de Soleil musical extravaganza: an expensive, but brilliant, piece of theatre: an homage to the music of the Beatles.

The Vegas experience was intense, but after that initial burst of incredulous pleasure, I was left peering into an empty box, wondering if something else would appear. It never did. All icing and no cake. Delighted to have been, but that will do me just fine, thank you. And goodbye.

We collected the car — a Hyundai Sonata, from the airport. I discovered that while we pronounce it Hi-‘n’-dye, the Americans just steam in with Hun-day. They don’t bugger about with superfluous vowels in fancy foreign words. Like Fanueil Hall in Boston, which we would pronounce Fan-way, but is Fan-you-ell to the locals. I quite admire their insolent phonetic iconoclasm. It’s only when the vandalism extends to meanings that I must protest. More of this in a moment.

Anyway the ‘Hunday’ was to be our companion for the next two weeks, and it did the job pretty well. A day or two navigating through the choked-up streets of Vegas was enough to remind me how the Americans drive (better than we do), but it’s first proper test was a 300-mile day, culminating with a bed in Tusayan, at the gates of the Grand Canyon.

En route, we drove across the engineering masterpiece of the Hoover Dam, before settling into an uneventful trip across the black, featureless plains of southern Nevada. The journey quickly reminded us of the USA beyond the confected Vegas. Driving south on the Interstate 93, we see a sign saying “Delicious Beef Jerky Available!” Feeling peckish, I suggested stopping, until we noticed the smaller lettering on the sign: “49 miles ahead”.

We did stop eventually, just short of Kingman, in a dusty geological saucer filled with trailers and not much else. We refuelled at a mom-and-pop gas station. Cheap petrol for the car, nuts and sweets and soda for us. Nothing fresh or nutritious to eat, though we were too hungry to care. I stood there in the hot sunshine, next to the torn poster flapping on the fence, gobbling peanuts and squinting at those tiny white boxes thrown across the parched, mustard landscape. People live in them — crikey. Vegas it aint.

Another long, sweet-suckin’ drive, this time east-west on Highways 66 and 40. We consider going crazy, but arrive at Williams just in time. This quirky little town, filled with folksy restaurants and variegated semiological puzzles, wakes us up again. We stop briefly, but need to get on to the Canyon, turning off the main road onto Highway 64 north.

It was now almost 6pm, and with nowhere to stay, we considered bed-hunting. But no, you don’t get many chances to see the sun set over the Grand Canyon, so we pressed on, reaching the reception centre with 30 minutes remaining before dark. We quickly picked the brains of the chap at the barrier, and headed off to his recommended spot.

It’s an odd thing. “Awesome” is a word now so overused in the US that it has ceased to have any meaning beyond “OK”. Here are two real examples heard on the current US trip:

— “I’ll give you a call at the weekend”

— “Awesome”.

— “If you want some ketchup, there’s some on the table behind you”

— “Awesome”.

And so another respectable, hard-working word, with its own place and its own meaning, crumbles into dust, ceasing to function as it ought. Why does this matter? It matters because when you visit the Grand Canyon, especially for the first time, you find yourself reaching for language to which you can tie your emotions; a word that will help you convey the pain of your delight to others who can’t be there with you. I want to describe my first sight of this magnificent geological phenomenon as “awesome”. It inspired awe in me. But I can no longer use that word, because now it means merely “OK”, or “Thanks”.

So just take it from me that had that word been available, it would have been perfect. As a gasp moment, it ranks alongside the Himalayas, and that own goal by Jamie Pollock for Manchester City in May 1998.

You should have been there. Maine Road, I mean. Invest a mere 7 seconds in this: … but no, wait. Let me first set the scene. It was at the end of dreadful 1998 season. Both City and QPR were struggling at the foot of the second tier. We went to City’s ground needing to get something to keep us alive. City had to win to stay up. With time running out and QPR losing 2-1, it was looking bleak. Then this happened: Pollock.

Astonishingly, it earned Jamie Pollock the accolade of “Greatest human being of all time” in a global internet poll. In a final surge characteristic of their own team’s season, delighted QPR fans got wind of the poll, and voted in large numbers to elevate Jamie above Jesus Christ and Mahatma Gandhi.

But I digress. The message is this: that the Grand Canyon looks like the edge of the world, and is as dramatic an experience as you could wish to have. We traced the rim of the canyon for 20 or 30 miles, stopping off at random points to gasp again. At one overlook, an elderly man standing near us muttered grouchily: “When you’ve seen it as often as I have, you realise it’s just another damn hole in the ground”. But I detected the shadow of a mischievous smirk as he said these words.

In a wholly different way, Phoenix, Arizona was a sort of awesome experience too. We arrived there in the dark after hours on the road. In we drove; around we drove; and out we drove, having seen almost no signs of life beyond the supine shapes sleeping in a forecourt that I used to do a U-turn. I don’t know who you are, but I almost killed you.

The city was dense with glowing skyscrapers, but the streets were empty of people, and there was barely a car to keep us company on the wide roads. Eerie and terrible. We left, stopping off a few miles out along Highway 10, at a Days Inn. Here we ate lime crisps and drank lime beer, and fell asleep quickly.

Which brings us to California.

A few hours further along Highway 10 we arrive at Joshua Tree National Park. A visit had been recommended by a couple of friends, so we opted to drive through it on our way to Palm Springs. I’m embarrassed to confess it, but at first, we found it rather empty and dull. But that becomes its point. Just like in Phoenix, we saw barely another car or human the whole time we were there; yet this was true wilderness. Compared with Phoenix, the positive sort. We stopped off every mile or two, got out of the car, and just listened. Nothing. How lovely, and how profound, to stand beneath the spindly fingers of the ocotillo cactus with its pretty scarlet flowers, in the heat of the desert, listening, but hearing nothing but a tumult of silence. Or was there just the subtlest buzzing of bees? A sound so delicate that it might have been carried on the breeze for miles, for all we knew. I thought of the Wellesley girls, and the distant hint of their presence.

Further along the track we see the fantastic cholla cactus gardens. These stumpy plants, casting off the curling, furry snakes of last year’s growth, were just coming into flower, and to see them spread across acres of the desert was to be reminded that even the most hostile of environments is brimming with creative activity. Think Shepherds Bush. We didn’t see the spiders and scorpions we were warned about. Nor did we see the biting bugs, but we felt them, and have been admiring their work ever since…

Then came the raucous drama of the joshua trees themselves. The headline act takes the stage late in the show; appearing with those mammoth boulders, sculpted by wind and time into smooth spheres, like giant, natural Henry Moores.

This sense of accidental art was repeated along the road 50 miles or so, in the spectacular approach to Palm Springs. Here in the shallow valley, an eternity of windfarm: beautifully co-ordinated, balletic. This too, we would once have called awesome.

Palm Springs is a warm and gentle town, a magnet for the wealthy elderly. Our hotel, the Palm Springs Tennis Club, was luxurious yet extremely cheap: another triumph for Tripadvisor. We strolled along main street, dipping into shops and seeking out the ideal place to eat. Eventually we alighted on Zin. Fine food, if pricey. Arriving back at the hotel, we found the local power company had cut the electricity to carry out maintenance. This plunged the area into a black, eerie, humid silence that would last until seven the next morning. The response of most people was to go to bed early, which I suspect wasn’t unusual for most of the residents. Palm Springs is genteel and understated. After sunset, you are unlikely to hear much beyond a grateful communal heartbeat and a gentle collective snore, like the distant buzzing of the bees in Joshua Tree.

But just as our holiday is drifting off to Lala Land on a downy cloud, with a beaming harpist plucking out our favourite lullabies… someone drops a million china plates and a million tin trays from a great height. Suddenly, we’re bolt upright and screaming for mercy.

Welcome to Los Angeles.

I may be old, but I’m not yet old enough for a Palm Springs funeral. Driving into Los Angeles, surveying the 12 lanes of high-speed traffic, adrenaline pumping, had me shouting and laughing with exhilaration. This was more like it. My first mouthful of LA madness, and how sweet it was. Thousands of us in our darting steel boxes, sunglasses and grim faces, not knowing you and not looking at you and not caring for you. We are all in the game, and we’re in it to win it. How extraordinarily exciting and energising to slip into that throbbing nest of furious ants, unnoticed. Pasadena, Hollywood, Ventura, Santa Monica: the signs made everything seem familiar, even though it was my first time here. I instantly loved it.

We had three good days there, happy to play minor roles: wide-eyed tourists. We did all the usual things, traipsing round Hollywood and Beverley Hills, and out to Venice Beach and Santa Monica. But there was one afternoon of particular joy. I found myself on my own. M wanted to visit the Paul Getty Museum, and I didn’t, so we amicably agreed to do our own thing. I dropped her off at the Getty, and sped off along Highway 101 to Pasadena. It was 26 miles of giggling freedom, and almost double that on the way back, as I happily allowed myself to get lost in the web of freeways that holds this city together, and that simultaneously keeps it separated from itself.

In the middle of those two trips, I tracked down the Academy cinema in Pasadena, one of only two places in LA still showing Clint Eastwood’s Gran Torino. I’d wanted to see the film for months but kept missing it at home. I was determined to catch it here. The Academy is the classic American flea-pit. Just two dollars to get in (three in the evenings). I paid my money, bought the one dollar hotdog and the huge bag of popcorn, and flopped into the back row. There were three others in the cinema when I got there. A fourth arrived just before the film started. She beamed at me as she passed: “Hi, I’m Barb!” I stared back. “Hi, I’m British”, and looked away.

No, I didn’t really. But I did in the comedy sketch invented around the incident later on.

I was spared any awkwardness by the start of the film, which was as life-affirming as I had been warned it would be. The movies allow us to escape, but linked to a rare afternoon of solitude, bordered by white-knuckle rides along the miles of LA freeways, this was a very fine afternoon indeed.

It was a relief to have seen the city at last, though it made less of an impression on me than San Francisco. We arrived there via the magnificent Pacific Coast Highway. Again, properly awesome. On the 2-day trip we had a night at the quaint Cambria, recommended by the venerable Glaconman, and in Monterey. The latter is pleasant enough, but try eating after 10 p.m. Californians are surprisingly diurnal. Someone explained to me that the time difference meant that they had to be up earlier to communicate with the rest of the business world, and this meant winding down earlier in the evening.

But San Francisco. What a very fine town this is, and a fitting way to end our US trip.

I’d driven like the clappers to get there, hoping to catch the Arsenal – Manchester United Champions League semi-final. I aimed for a pub in Haight Street that I’d read would be showing it: the Dog in the Fog. By the time we got there, it was already 3-0 to the Rowdies, and so I didn’t stay. The contest was finished. The decision to leave was made easier by a bunch of loud and hostile Northern Irish fans. At least I think they were being hostile. It’s not always easy to tell.

San Francisco doesn’t have the disorientating sprawl of Los Angeles. You know where you are with compactness. The city has a sense of refinement and integrity, and a heart and soul I didn’t notice in its southern sister. It took only an hour or two of driving round to understand where things are, how the districts fit together, and how to get where we needed to get, navigating through the neat grid of streets, within 20 minutes or so. And you have the constant oooh-aaaah entertainment of the stupendous roller-coaster hills and the quaint old trams, some of them 90 years old.

Again, we checked off the usual shopping list of tourist treats, taking the ferry out to Alcatraz and the ancient painted tram along the seafront. We drove to Golden Gate Bridge, walked in the great parks, pottered round Fisherman’s Wharf and Chinatown.

I also found time to walk in the footsteps of Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady, and to visit some of their hangouts. It was a neat role-reversal as Kerouac has haunted my own life for so long. I’m afraid I’m one of those people who read On The Road when I was 15, and found myself confronting an utterly new world from that day forward.

Still on the path of the Beat Generation, I achieved a long-held ambition: to visit the famous City Lights bookshop, and buy a new copy of Howl, Allen Ginsberg’s great beat poem of 1956. It was City Lights who first published the work, and whose owner, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, faced, and won, an obscenity trial for his pains. The poem takes me back 27 years or so, when I shared a student house with like-minded dreamers. Our ancient copy of Howl fell apart in the end; it was read and passed around so much. It opens:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by

madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn

looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly

connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night

….

We were nice middle class boys in the main, but oh how we fancied ourselves as ‘angelheaded hipsters’, hung out to dry by Thatcher and her bourgeois collaborators. Quite funny looking back, but it’s still indisputably a great poem, and one that says as much about the Beats as On The Road. If you have a spare hour, you know what to do. Prepare to be whipped and wounded by the power of words.

Another high spot of our time in San Francisco was meeting up with my work colleague, Mary, and her husband Ed, down in Haight, where they live. A fun area, reminiscent of Ladbroke Grove, or Notting Hill in its pre-gentrification heyday. Fine old houses, a minestrone of ethnicities, and a pleasing air of intellectual independence. It’s tempting to think of it as anarchic, but it’s more organised than that. More like quirky self-government.

We met in a bar, where I collected another magnificent Bloody Mary. How I love this drink, and its unique ability to deliver a sledgehammer thwack to the side of the head, just as I am beginning to flag, or to help chase away a hangover from the previous night. Not that either circumstance was present here. Instead, I was using its third gift: the pure pleasure offered by the cocktail of flavours and physical sensations: Tabasco and tomato and Worcestershire Sauce and black pepper and salt. Oh yes, and alcohol, though the presence of the vodka is often lost beneath the more piquant smack of the spicier ingredients. Americans make bloody good Bloody Marys, as I noted at various bars and eateries from Vegas onwards. The only place that couldn’t deliver was a curious Mexican steak house in Tusayan, Arizona, where the barman had shaken his head with a sour pout that had unspokenly growled: “We don’t do poncey gringo cocktails here”.

We had a good evening with Mary and Ed, moving onto a Brazilian restaurant where we got mildly drunk on pokey sangria. I swapped Buddhist observations with Mary’s husband. “We are scared of the snake”, he said. “But sometimes, if we get closer, we see it is just a stick. Our task is to understand that all our snakes are really nothing more than sticks.”

I am reminded of a similar sentiment donated by my sister: “The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure that you seek“. A good marathon motto.

It’s time to end this extended race report, and noting these life-affirming mantras is a good way to do it. Thinking about the messages starts a train of thought that stops first at Room 210 at the marathon expo, where I recall similar attitudes being expressed by the “Boston Legends”. I think it was Fultz who said that “success is not a goal but a lifestyle”. My boss will like that one. I’ll be sure to slip it into a conversation at a strategic point, and await the admiring nods of approval.

Since I heard his compelling narration of the tale, I’ve often considered Amby Burfoot’s chasing shadow. For a while, I wondered if it was a metaphor, but I checked, and found that the struggle with Bill Clark was real enough. Yet it didn’t have to be. When thinking about our own, more humble marathon campaigns, it strikes me that we have similar fights, and pursuits, against similar opponents. They are rarely real, yet these metaphysical enemies threaten to consume us. And sometimes do. I had my own fears to contend with this time around, as always. Injuries and self-doubt. But like Heartbreak Hill, they turned out to be something and nothing.

Isn’t that always the way?

|

|

|